I have

previously briefly mentioned a couple of problems with the new work

Kuntress Ha-Teshuvot haHadash, now I would like to give a full review. First, I am no expert in the teshuva literature, that being said I was somewhat disappointed with this book.

The book first contains a long introduction into the teshuva literature in general. It discusses such topics as the importance of the literature, the pervasiveness or lack there of, as well as censorship in the teshuvot and different bibliographic topics. On this last point, the introduction discusses how, at the advent of printing, teshuvot do not seem to have been that important. They come do this conclusion by comparing amounts of other types of books printed during the same period with that of teshuvot. Books on other topics were printed in mass, while teshuvot made up only a very small portion of the books printed.

The introduction is fairly informative, although for much of this ground there are far better works out there (documented in the extensive footnotes), this does provide a basic understanding. Finally, there is a discussion about the book itself and what Boaz Cohen’s work (the predecessor to this one) is out to accomplish. This last topic is also covered in an English translation of the introduction, however, all the rest of the introduction is not translated.

The bulk of the book is devoted to the actual bibliographical entries of the teshuva books. This volume covers books with titles between aleph and lamed. But it is far from clear what exactly the standard for these entries are. If I had to categorize my main complaint with this, it would unevenness. That is, for some entries there is a significant amount of information such as some important teshuvot from that book, what other books discuss this one, and other points of interest. For other books with equally important and interesting teshuvot there is nothing.

So for

Luach Eres by R. Jacob Emden (no. 1950) there is a long entry dealing with all the content of the work as well as others who he discusses and those who discuss the work as well. They also include articles on the book as well. This runs over three densely packed columns. The same is true for

Eleh Divrei HaBrit (no. 222) as well as many, many others.

But for the book

Har Tabor (no. 1129) which discusses the proper place of the bimah in the center of the synagogue there is no mention of any other books which discuss this topic, or any other books which disagree with this book either.

Another example, the book

Be’ar Esek (no. 406) contains a teshuva about the R. Menacham of Fano and whether he had a beard. This teshuva was highly controversial and R. Yosef Erges, R. Moshe Sofer, and R. Eliazer of Munkatz all wrote about it. There is no mention of this teshuva in the entry nor is there any mention of the literature this teshuva spawned.

This last point, that at times they fail to reference other books about the one entered happens time and time again. Perhaps the most egregious example of this is the

Divrei Iggeret by R. Menhem Steinhardt (no. 759). Although the entry does note this book contains a teshuva on kitnyot (he permits it) it doesn’t mention any of the books discussing this topic, e.g. Ashro Hametz (which has no entry at all), nor does it mention the teshuva from R. Moses Sofer against R. Steinhardt’s permitting kitnyot. Additionally, it doesn’t mention an article devoted to the book itself. Professor Judith Bleich wrote an article titled “Menahem Mendel Steinhardt’s "Divrei Iggeret", Harbinger of reform” in the

Proceedings for the World Congress of Jewish Studies 10 (1990): 207-214.

The next problem with the work is incompleteness. This is apparent in the entries as well as the bibliography provided. So some of the problems mentioned above are the worst, in that they don’t list anything about the book, at times even when they do they do a shoddy job. Already in my previous post I mentioned the poor entry on the organ. But there are numerous others. For instance, they have a fairly comprehensive entry on the book

Hayi Olam (no. 1456) which deals with the issue of cremation. They discuss the content of the book as well as others who disagree with the author. They list other books dealing with the same subject matter as well. However, they fail to mention Michael Higger’s coverage (perhaps the most comprehensive) on this topic. (This appears in his

Halakhot ve’Aggadot, 1933).

Or we have the entry for Modena’s works. Perhaps it is worthwhile to compare this entry with another. We first have the entry for the

Zakan Ahron by R. Ahron Walken. As each entry includes biographical information and sources this entry reads “על המחבר ראה: דור רבניו וסופריו, ו, עמ' 31-32; אהלי שם, עמ' 201; אנציקלופדיה של הציונות הדתית, ב, עמ' 175-177. וראה לאחרונה, אליעזר הכהן כ"צמאן, "נעימות התורה- הג"ר אהרן וואלקין אב"ד פינסק בעל בית אהרן, זקן אהרן, וכו'", ישורון יא (תשס"ב), עמ' תתצא-תתקד; יב (תשם"ג) עמ' תשכז-תשלט." So, for this we have three entries plus a recent article discussing the biographical details. Now we turn to Modena. For Modena we have the following: “על המחבר ראה "אריה ישאג – ר' יהודה אריה מודינה ועולמו” and then provides the detail for that book. So we have one entry for Modena biography. So was Modena unknown? No, far from it, he wrote his own autobiography. There have been numerous articles on him as well as a full lengthy doctoral dissertation by Adelman. His autobiography is available in both Hebrew and English. The English version contain articles on him as well. But none of these are mentioned.

Now we get to omissions. The book

Avot ‘Atrarah L’Banin (no. 4) contains, as the entry notes, an extensive teshuva on the permissibility of being photographed. It includes a list of Rabbis who had their photograph or more likely, their portrait done. This is all well and good. However, the entry leaves out perhaps the most interesting part, the author of Avot included a photograph (loose) of himself in the first edition. Thus, his teshuva was in a sense to justify his own practice.

There is no entry for the book

Hadrat Panin Zakan which is a collection of teshuvot on beards. Nor is there an entry for the book

Da’as HaRabanim which is two long teshuvot from R. Menachem Mendal Kasher and R. D. Polonski (

Kli Hemdah) discussing women’s suffrage.

The editors claim this list only goes up to the year 2000. However, for some entries they include editions even after the year 2000. For R. Yehudah Herzl Henkin’s

Beni Banim (no. 555) they include his fourth volume printed in 2004. However, for R. Teichtel’s

Em HaBanim Semacha (no. 239) where there have been two recent translations which are different they do not include this. But again for R. Menachem Kasher’s

Hatekufa haGedolah (no. 1144) (how this even qualifies as a teshuvah book is left unanswered) they include his 2001 edition.

Or we have the entry for the

Helkat Ya’akov (no. 1496) where they note the first edition date and then the rest they claim are photo-offsets of the original. This is wrong. In the subsequent editions R. Herzog’s approbation was removed and thus they are not just copies of the original.

However, perhaps the answer to some of these shortcomings comes from the introduction itself. The editors explain how this work came to be. They explain that this was initially an "auxiliary tool for another project" a project on "Jewish education in the halakhic literature." This is perhaps most telling. They are explaining to the reader that

(a) they are not bilbiographers;

(b) they did not initially set out to do this;

(c) they are not experts in teshuvot. These shortcomings are apparent. This being said, it is important to recognize that this is a vast improvement over Cohen's work and a welcome entry for Jewish biliography.

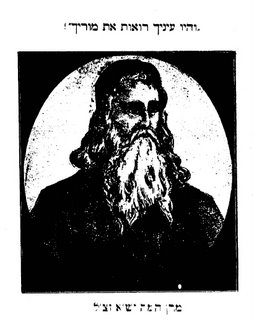

To the left are pictures what are supposed to be the Klausenberger Rebbe burning the book HaGaon (discussed here previously) with the Hametz. Additionally the final picture is him saying the Yehi Ratzon from the Ateresh Yehoshua when burning books of heresy. If you click on the images you can see them enlarged. Here is the full text of the Yehi Ratzon

To the left are pictures what are supposed to be the Klausenberger Rebbe burning the book HaGaon (discussed here previously) with the Hametz. Additionally the final picture is him saying the Yehi Ratzon from the Ateresh Yehoshua when burning books of heresy. If you click on the images you can see them enlarged. Here is the full text of the Yehi Ratzon