An astute reader emailed me that it appears the new and improved edition of Making of a Godol has been banned. Although this edition attempted to "fix" some of the "problems" of the first, it appears that it has not satisfied it detractors. See here. I hope to get a copy of the letter referenced in the article, when I do I will post it.

↧

Making of a Godol Banned - Again

↧

Upcoming Auctions

There are three upcoming auctions. Two of those have their catalogs online. Kestenbaum whose auction will happen this Thursday has some very nice pieces, including R. Hirsch's manuscript on Devarim est. $50,000, you can view the catalog here. And Asufa will have their auction this Sunday the 26th, and their catalog is here. They also have some unique pieces, well worth checking out. The final auction is Jerusalem Judaica which will take place the 30th but unfortunatly their catalog is not online so you will have to find a store which carries it (Biegeleisen has it).

↧

↧

Text of the New Ban on Making of a Godol

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. A helpful reader has scanned the Yated with the latest ban against Making of a Godol ("MOAG"). It is notable that R. Eliashiv has signed again as have others who were part of the original ban. Also, as you can see this appeared on the top of the front page as well as a separate article. Those who signed claim that this edition of MOAG although ostensibly "fixed" the "problems" it was unsuccessful and they state "the second edition is the same as the first." Addtionally, the orignal ban is reprinted with a note that it is still in force. You can click on the scans for a larger view. For some of the differences between MOAG I and MOAG II see here, here and here.

A helpful reader has scanned the Yated with the latest ban against Making of a Godol ("MOAG"). It is notable that R. Eliashiv has signed again as have others who were part of the original ban. Also, as you can see this appeared on the top of the front page as well as a separate article. Those who signed claim that this edition of MOAG although ostensibly "fixed" the "problems" it was unsuccessful and they state "the second edition is the same as the first." Addtionally, the orignal ban is reprinted with a note that it is still in force. You can click on the scans for a larger view. For some of the differences between MOAG I and MOAG II see here, here and here.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

A helpful reader has scanned the Yated with the latest ban against Making of a Godol ("MOAG"). It is notable that R. Eliashiv has signed again as have others who were part of the original ban. Also, as you can see this appeared on the top of the front page as well as a separate article. Those who signed claim that this edition of MOAG although ostensibly "fixed" the "problems" it was unsuccessful and they state "the second edition is the same as the first." Addtionally, the orignal ban is reprinted with a note that it is still in force. You can click on the scans for a larger view. For some of the differences between MOAG I and MOAG II see here, here and here.

A helpful reader has scanned the Yated with the latest ban against Making of a Godol ("MOAG"). It is notable that R. Eliashiv has signed again as have others who were part of the original ban. Also, as you can see this appeared on the top of the front page as well as a separate article. Those who signed claim that this edition of MOAG although ostensibly "fixed" the "problems" it was unsuccessful and they state "the second edition is the same as the first." Addtionally, the orignal ban is reprinted with a note that it is still in force. You can click on the scans for a larger view. For some of the differences between MOAG I and MOAG II see here, here and here.↧

Plagiarism I

As some of you have brought up in the comments regarding other works that had been plagiarized I thought it would be appropriate to discuss some of the more famous and those less so of instances of plagiarism.

The first example, is perhaps the most well-known one, that of the work Mekore Minhagim. This work which in question and answer form, discusses the sources and reasons for various customs was first printed in 1846 in Berlin by R. Avrohom Lewysohn (1805-1861). This work contained 100 of these questions and answers and consequently ended with a , ויזרע אברהם מאה שערים ויברכו ה and Avrohom planted 100 gates. This, of course referenced the authors name and the fact he wrote 100 questions. This is lifted from the verse in Genesis 26:12 ויזרע יצחק . . .מאה שערים ויברכו ה.

However, if today one tries to purchase this book (any one still can it has been reprinted many times) instead of a photocopy of the 1846 edition by Lewysohn, one gets a book with the same title but the author's name is actually Yosef Finkelstein (originally published in Vienna in 1851). Also, instead of 100 questions there are only 41. Those differences aside, the remaining 41 questions and answers are word for word the same as Lewysohn's.

This plagiarism was noted almost immediately in MGWJ vol. 1, 1852 p. 34(available here.) However, this did not stop Finkelstein, and his edition was published possibly twice in 1851 alone and from then on numerous times to this day.

While Finkelstein's is word for word, he was forced to change a few minor things. One in particular was the play on the verse at the end, his reads, ויזרע ויסף מא' שערים. Although he attempted to retain the play on the verse, this fails as there was only 41 gates in his edition.

Finkelstein did not stop there. When his treachery was revealed in the paper HaMagid, he actually went on to argue that it was Lewysohn who copied from him and not the other way around. Finkelstein claimed when he was passing through Berlin, Lewysohn asked to borrow his manuscript and surreptitiously copied it. Finkelstein, however, does not explain how Lewysohn was able to add the additional 59 question and answers. Additionally, we will see in the next installment on this book, how Finkelstein gives himself away.

For more on plagiarism especially the halakhic discussion see here.

The first example, is perhaps the most well-known one, that of the work Mekore Minhagim. This work which in question and answer form, discusses the sources and reasons for various customs was first printed in 1846 in Berlin by R. Avrohom Lewysohn (1805-1861). This work contained 100 of these questions and answers and consequently ended with a , ויזרע אברהם מאה שערים ויברכו ה and Avrohom planted 100 gates. This, of course referenced the authors name and the fact he wrote 100 questions. This is lifted from the verse in Genesis 26:12 ויזרע יצחק . . .מאה שערים ויברכו ה.

However, if today one tries to purchase this book (any one still can it has been reprinted many times) instead of a photocopy of the 1846 edition by Lewysohn, one gets a book with the same title but the author's name is actually Yosef Finkelstein (originally published in Vienna in 1851). Also, instead of 100 questions there are only 41. Those differences aside, the remaining 41 questions and answers are word for word the same as Lewysohn's.

This plagiarism was noted almost immediately in MGWJ vol. 1, 1852 p. 34(available here.) However, this did not stop Finkelstein, and his edition was published possibly twice in 1851 alone and from then on numerous times to this day.

While Finkelstein's is word for word, he was forced to change a few minor things. One in particular was the play on the verse at the end, his reads, ויזרע ויסף מא' שערים. Although he attempted to retain the play on the verse, this fails as there was only 41 gates in his edition.

Finkelstein did not stop there. When his treachery was revealed in the paper HaMagid, he actually went on to argue that it was Lewysohn who copied from him and not the other way around. Finkelstein claimed when he was passing through Berlin, Lewysohn asked to borrow his manuscript and surreptitiously copied it. Finkelstein, however, does not explain how Lewysohn was able to add the additional 59 question and answers. Additionally, we will see in the next installment on this book, how Finkelstein gives himself away.

For more on plagiarism especially the halakhic discussion see here.

(Continued here)

↧

Latest MOAG Ban Runs Counter to an Agreement with R. Eliyashiv

Image may be NSFW.

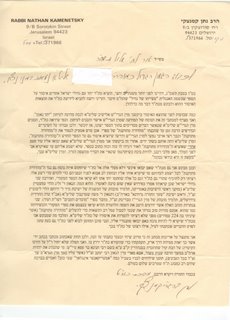

Clik here to view.![]() A reader has sent me the following letter from R. Kamenstky discussing the possiblity of a ban on the improved edition of MOAG. The letter says "if people will come to complain to R. Eliasiv about the new edition and say such and such is written there, he will not listen to them until he first calls me, and I will need to present when they translate my book for him."

A reader has sent me the following letter from R. Kamenstky discussing the possiblity of a ban on the improved edition of MOAG. The letter says "if people will come to complain to R. Eliasiv about the new edition and say such and such is written there, he will not listen to them until he first calls me, and I will need to present when they translate my book for him."

Additionally, I have received the following relevant information.

Clik here to view.

A reader has sent me the following letter from R. Kamenstky discussing the possiblity of a ban on the improved edition of MOAG. The letter says "if people will come to complain to R. Eliasiv about the new edition and say such and such is written there, he will not listen to them until he first calls me, and I will need to present when they translate my book for him."

A reader has sent me the following letter from R. Kamenstky discussing the possiblity of a ban on the improved edition of MOAG. The letter says "if people will come to complain to R. Eliasiv about the new edition and say such and such is written there, he will not listen to them until he first calls me, and I will need to present when they translate my book for him."Additionally, I have received the following relevant information.

"The letter quotes Rav Elyashiv as saying that the request that the author should be called and given a fair chance to defend himself is just. This was repeated by a number of meetings that the author had with R' Elyashiv. Before the letter was sent out it was shown to Aryeh Elyashiv - the grandson in charge of all the appointments and present in the room during all meetings to assist his grandfather - and he stated that the quote was correct and it conveys faithfully his grandfather's say on the matter.

The letter was delivered to the following Rabbis:

Steinman

Sheinberg

Karelitz

Kanyevsky

Markowitz

Auerbach

It was not sent to Rabbi Shapiro because he already apologized for the first time that he signed against the book, and had already said that he will not have anything more to do with this affair. Sure enough he kept his word now and didn't sign.

R' Wolbe was omitted because he's not alive.

R' Elyashiv didn't have to receive this letter because he was the subject of the letter.

R' Lefkowitz was not sent this letter because he was very vicious the time before, and could not be expected to be fair.

The author has made it his habit to daven in the morning in R' Elyashiv's minyan from time to time, so that if anything arises he can be informed of immediately.

This last Friday and Sunday he was at the minyan and no one (including Yisroel Elyashiv - another grandson) said anything when asked if everything is fine. It was only after he came home that he found out about the ad and article in Yated Neeman."

↧

↧

Plagiarism II (Talmudic Terminology)

In 1988, Rabbi Nosson Dovid Rabinowich published a book titled Talmudic Terminology. However, as was noted in brief by Dr. Marc Shapiro, this was plagiarized from Moses Mielziner's Introduction to the Talmud, first published in 1894. This omission, however, has been corrected in Rabinowich's reprints of his Talmudic Terminology where the title now reads that Rabinowich's work is "adapted" from Mielziner's.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

While this would appear to be the end of the matter it is not. Dr. Shapiro has investigated this issue further and has sent the following:

Additionally, in an effort to keep the two "editions" the same, Rabinowich did not alter the pagination, this is so, even though he removed the haskamot. Consequently, the "new" edition is missing those pages. I have provided both title pages as well as Rabbis Yosef's and Feldman's haskamot (as one can no longer get them).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

While this would appear to be the end of the matter it is not. Dr. Shapiro has investigated this issue further and has sent the following:

After I published my book on Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox a number of people pointed out to me that Nosson Rabinowich's plagiarism of Mielziner is more extensive than what I point out. I didn't know what they were referring to since I had the first edition of his book M. Mielziner's Talmudic Terminology, published in 1988 (in my kuntres there is a typo, as it says 1998). Or so I thought. I succeeded in locating another copy by interlibrary loan, and lo and behold, the title page does not say M. Mielziners Talmudic Terminology adapted by N. Rabinowich but it identifies him as the author. What's even more fascinating is that the other edition has haskamot of Rabbis Ovadiah Yosef and Aharon Feldman. Obviously when the scandal broke, Rabinowich quickly produced a new title page and took out the haskamot (and also added a note on p. xv and made a slightchange in note 2 on. p. xv (replacing "some" with "most".) It is obvious why the haskamot were taken out, since they praise Rabinowich for producing a book which he didn't write. In fact, Rabinowich is responsible for something very interesting. We find here the first example in history where gedolim put a haskamah on a work written by a Reform rabbi! Unknowingly Rabbis Yosef and Feldman gave a haskamah to Mielziner. You can be sure this is not something that makes them happy.Additionally, in an effort to keep the two "editions" the same, Rabinowich did not alter the pagination, this is so, even though he removed the haskamot. Consequently, the "new" edition is missing those pages. I have provided both title pages as well as Rabbis Yosef's and Feldman's haskamot (as one can no longer get them).

Additionally, in an effort to keep the two "editions" the same, Rabinowich did not alter the pagination, this is so, even though he removed the haskamot. Consequently, the "new" edition is missing those pages. I have provided both title pages as well as Rabbis Yosef's and Feldman's haskamot (as one can no longer get them).

↧

Dei'ah veDibur on the MOAG Ban

↧

Review of Where there's Life there's Life

Rabbi David Feldman, who is well known for his book on issues relating to Jewish law and the beginning of life (abortion, birth control etc.), has now published via Yashar Books, a book on end of life issues and Jewish law. This book covers such topics as reproductive technology, stem cells, organ transplants, suicide, and determining death. Although it covers such weighty topics it is a rather easy read. Rabbi Feldman eschews highly technical discussion and instead has opened the book for everyone. Each topic gets about ten pages of treatment and Rabbi Feldman lays out the basic principles underlying each of these issues.

He begins with an extensive introduction on pikuach nefesh which much of the subsequent discussions are premised upon. The book is a little over 130 pages, which means none of the topics are treated in great depth. However, as Rabbi Feldman states in the introduction his purpose was not to provide a comprehensive book on the topic, rather to give some general guidance on this hot button issues. In this area he succeeds. He does provide a very basic introduction to the topics and does provide some of the key sources. Consequently, one who reads this book will have the basics to further investigate these issues.

However, with this approach there are some significant draw backs. Rabbi Feldman, while stating what he feels the commentaries say, does not provide sources for these. He give almost no citations to any source he quotes (there are two exception to this, once he gives a citation to R. Feinstein's responsum and once he gives a cite to a responsum from R. Moshe Sofer). For example, when discussing organ transplants he tells us the key responsum is from R. Yechezkel Landau (Noda Biyehudah) where he holds when the organ donor is "in front of us." That is, on a simple level, one can only do a transplant when one has a ready person to accept the organ. Rabbi Feldman then goes on to discuss others who have applied this statement all without ever providing where R. Landau said it, nor where the subsequent discussion can be found. This seriously hampers any follow up a reader wishes to do or for that matter, to ensure Rabbi Feldman's reading is the correct reading.

To be fair, Rabbi Feldman does offer that is one contacts him via email he will provide citations and additional sources, however, his email doesn't appear anywhere in the book. Assuming these citations were omitted to enable easier reading, why they could not be included on a page or two at the end I do not understand. Instead, we are left to blindly trust Rabbi Feldman in his assessment of the sources.

Further, Rabbi Feldman is far from the first to write on these topics. Instead, a simple search of RAMBI one can see there are numerous articles on all of these topics, none of these are provided. While Rabbi Feldman is not obligated to cite the works of others, it is difficult to understand Rabbi Feldman's claim that "the need to address [these issues] is both urgent and constant," as these very issues have been already comprehensively discussed by many, many others.

Additionally, as I mentioned previously, this book does provide an excellent starting point for these discussions. We are bombarded with many who claim to know what the Bible says for these important topics, but most are blissfully unaware of what the Bible and more specifically Jewish law says and has said about these topics, this cures that. But, it is hard to say it will facilitate further discussion when one doesn't know where to go next.

In the end, this book, in a clear and straightforward manner, if a bit curt, which provides the groundwork for understanding extremely important issues regarding the end of life and new technologies relating that implicate life and death.

He begins with an extensive introduction on pikuach nefesh which much of the subsequent discussions are premised upon. The book is a little over 130 pages, which means none of the topics are treated in great depth. However, as Rabbi Feldman states in the introduction his purpose was not to provide a comprehensive book on the topic, rather to give some general guidance on this hot button issues. In this area he succeeds. He does provide a very basic introduction to the topics and does provide some of the key sources. Consequently, one who reads this book will have the basics to further investigate these issues.

However, with this approach there are some significant draw backs. Rabbi Feldman, while stating what he feels the commentaries say, does not provide sources for these. He give almost no citations to any source he quotes (there are two exception to this, once he gives a citation to R. Feinstein's responsum and once he gives a cite to a responsum from R. Moshe Sofer). For example, when discussing organ transplants he tells us the key responsum is from R. Yechezkel Landau (Noda Biyehudah) where he holds when the organ donor is "in front of us." That is, on a simple level, one can only do a transplant when one has a ready person to accept the organ. Rabbi Feldman then goes on to discuss others who have applied this statement all without ever providing where R. Landau said it, nor where the subsequent discussion can be found. This seriously hampers any follow up a reader wishes to do or for that matter, to ensure Rabbi Feldman's reading is the correct reading.

To be fair, Rabbi Feldman does offer that is one contacts him via email he will provide citations and additional sources, however, his email doesn't appear anywhere in the book. Assuming these citations were omitted to enable easier reading, why they could not be included on a page or two at the end I do not understand. Instead, we are left to blindly trust Rabbi Feldman in his assessment of the sources.

Further, Rabbi Feldman is far from the first to write on these topics. Instead, a simple search of RAMBI one can see there are numerous articles on all of these topics, none of these are provided. While Rabbi Feldman is not obligated to cite the works of others, it is difficult to understand Rabbi Feldman's claim that "the need to address [these issues] is both urgent and constant," as these very issues have been already comprehensively discussed by many, many others.

Additionally, as I mentioned previously, this book does provide an excellent starting point for these discussions. We are bombarded with many who claim to know what the Bible says for these important topics, but most are blissfully unaware of what the Bible and more specifically Jewish law says and has said about these topics, this cures that. But, it is hard to say it will facilitate further discussion when one doesn't know where to go next.

In the end, this book, in a clear and straightforward manner, if a bit curt, which provides the groundwork for understanding extremely important issues regarding the end of life and new technologies relating that implicate life and death.

↧

The Ban on the book HaGaon

Image may be NSFW.

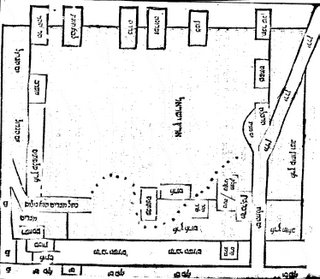

Clik here to view.![]() Now, as the Yiddish newspaper Der Yid has gotten around to commenting on the book HaGaon, I thought it would be worthwhile flesh out the entire controversy surrounding this book. Interestingly, R. Kamentsky in Making of a Godol actually discusses this very topic, although not in the context of HaGaon.

Now, as the Yiddish newspaper Der Yid has gotten around to commenting on the book HaGaon, I thought it would be worthwhile flesh out the entire controversy surrounding this book. Interestingly, R. Kamentsky in Making of a Godol actually discusses this very topic, although not in the context of HaGaon.

HaGaon written by R. Dov Eliakh in three volumes discusses everything and anything having to do with the Vilna Gaon. Most of the book is not controversial at all, instead, in painstaking detail R. Eliakh chronicles what we know about the Gra and the times he lived in. However, the third volume was the one that many took issue with. That volume, which discusses the controversy between the hassidim and the non-hassdim, also includes most of the primary literature on the topic. That means, R. Eliakh quotes extensively from many of the early anti-hassidic tracts which were published. Some of these contain scathing critiques of the hassidim and accuse them of rather disturbing acts.

However, as many are aware this was not the first time these were published. All of these, and more, have been published by Mordecai Wilensky, in his Hasidim u-Mitnagdim (which is now available again). In fact, much of this has even been translated into English in Elijah Schochet's The Hasidic Movement and the Vilna Gaon. But, for some who are unaware of these, Eliakh's book was highly disturbing.

The main complaints came, as is not a surprise, from hasidic circles. For instance, in the magazine Olam haHasidut, has three issues devoted to the book. On the cover of two of those issues, the book HaGoan appears in flames. Needless to say they were not fans of the book. The title reads אוי לדור שכך עלתה בימיו (how unfortunate we are to have this happen in our time). Among the major complaints about the book is that it is "written in the style of the maskilim (enlightenment)." I assume that means that as Eliakh documented everything he wrote that is in the style of the maskilim.

Additionally, they complain that as this controversy is no longer applicable (as the hasidim of today don't do what they did back then), it serves no purpose in relating this again.

Now, here is where Making of a Godol comes in. R. Nathan Kamenetsky records what his father, R. Yaakov's opinion on whether to discuss the history of the controversy between the hasidim and the non-hasidim. "My father [R. Yaakov] approved of snubbing of 'a book on the Goan of Vilna by an outstanding author' because 'the author had purposely omitted chapters dealing with the Gaon's opposition to Hasiduth and that he [R. Yaakov] said, 'It is prohibited to conceal substantive and important issues such as these. Such distortion is tantamount to falsehood.'" R. Nathan Kamentsky goes on to relate that the book in question was R. Landau's biography of the Gra and that his father [Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky] actually confronted R. Landau and accused him of "falsifying the image of the Gaon." See Making of a Godol vol. 1 pp. xxvii (available here).

Consequently, R. Yaakov felt that leaving out such a seminal fact in a biography was equivalent to lying. However, as we see, the publishers of Olam haHassidut appear to disagree. They are not the only ones. R. Yaakov Perlow, the Novominsker Rebbi, wrote a long article where he also takes issue with Eliakh's book. He also claims that R. Eliakh should have left out the details of the controversy.

It would appear that there is a fundamental controversy as to whether or not one should lie regarding history. In fact, in the journal Ohr Yisrael, there was an article addressing this very point - whether one should lie to tell stories that create yirat shamyim. The author concludes "if the teacher is telling stories which are not true, but is doing so leshem shamyim, so long as he doesn't make a habit out of it, there is a place to be lenient in this matter, however, one should try to minimize this."

Interestingly, in the next volume the Admor from Slonim has a stinging rebuttal of the article. He starts by saying, "Our tradition is based upon truth . . . how terrible it is to inject lies into our tradition." He then explains such a view undermines our entire religion "whomever permits [one to lie] it is as if he is creating uncertainty in the truth of our entire tradition, which is based upon the passing from generation to generation. My teachers have taught that one should only accept truthful stories."

So it would appear that there is an ongoing controversy, one which implicated the book HaGaon, with some arguing lying or covering up fundamental historical facts, is ok. While others claim this is totally unconscionable.

Sources: Olam haHassidut no. 88, Shevat 2002; 89, Adar 2002; 90, Nissan, 2002. Rabbi H. Oberlander, "HaIm Mutar l'Saper Ma'siyot shaninom amitim kedi l'orrer al yedi zeh l'Torah v'lyerat shaymim, Ohr Yisrael, 29 p. 121-123; R. Avrohom Weinberg (Admor M'Slonim Beni Brak), Letter, Ohr Yisrael, 30, 244. See also, Ari Zivotofsky, Perspectives on Truthfulness in the Jewish Tradition, Judaism 42:3 (Summer, 1993): 267-288. R. Yaakov Perlow, Yeshurun vol. 10 starting on page 831. Der Yid, Talumat Seftei Sheker haDovrot al Tzadik Atik, March 17, 2006. See also here for a discussion of the book. There are others that discuss this as well, and in R. Nathan Kamenetsky's introduction he quotes them. Further, as a helpful reader/movie buff has noted, I should have included R. Dr. Jacob J. Schacter's article on this topic available here.

Clik here to view.

Now, as the Yiddish newspaper Der Yid has gotten around to commenting on the book HaGaon, I thought it would be worthwhile flesh out the entire controversy surrounding this book. Interestingly, R. Kamentsky in Making of a Godol actually discusses this very topic, although not in the context of HaGaon.

Now, as the Yiddish newspaper Der Yid has gotten around to commenting on the book HaGaon, I thought it would be worthwhile flesh out the entire controversy surrounding this book. Interestingly, R. Kamentsky in Making of a Godol actually discusses this very topic, although not in the context of HaGaon.HaGaon written by R. Dov Eliakh in three volumes discusses everything and anything having to do with the Vilna Gaon. Most of the book is not controversial at all, instead, in painstaking detail R. Eliakh chronicles what we know about the Gra and the times he lived in. However, the third volume was the one that many took issue with. That volume, which discusses the controversy between the hassidim and the non-hassdim, also includes most of the primary literature on the topic. That means, R. Eliakh quotes extensively from many of the early anti-hassidic tracts which were published. Some of these contain scathing critiques of the hassidim and accuse them of rather disturbing acts.

However, as many are aware this was not the first time these were published. All of these, and more, have been published by Mordecai Wilensky, in his Hasidim u-Mitnagdim (which is now available again). In fact, much of this has even been translated into English in Elijah Schochet's The Hasidic Movement and the Vilna Gaon. But, for some who are unaware of these, Eliakh's book was highly disturbing.

The main complaints came, as is not a surprise, from hasidic circles. For instance, in the magazine Olam haHasidut, has three issues devoted to the book. On the cover of two of those issues, the book HaGoan appears in flames. Needless to say they were not fans of the book. The title reads אוי לדור שכך עלתה בימיו (how unfortunate we are to have this happen in our time). Among the major complaints about the book is that it is "written in the style of the maskilim (enlightenment)." I assume that means that as Eliakh documented everything he wrote that is in the style of the maskilim.

Additionally, they complain that as this controversy is no longer applicable (as the hasidim of today don't do what they did back then), it serves no purpose in relating this again.

Now, here is where Making of a Godol comes in. R. Nathan Kamenetsky records what his father, R. Yaakov's opinion on whether to discuss the history of the controversy between the hasidim and the non-hasidim. "My father [R. Yaakov] approved of snubbing of 'a book on the Goan of Vilna by an outstanding author' because 'the author had purposely omitted chapters dealing with the Gaon's opposition to Hasiduth and that he [R. Yaakov] said, 'It is prohibited to conceal substantive and important issues such as these. Such distortion is tantamount to falsehood.'" R. Nathan Kamentsky goes on to relate that the book in question was R. Landau's biography of the Gra and that his father [Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky] actually confronted R. Landau and accused him of "falsifying the image of the Gaon." See Making of a Godol vol. 1 pp. xxvii (available here).

Consequently, R. Yaakov felt that leaving out such a seminal fact in a biography was equivalent to lying. However, as we see, the publishers of Olam haHassidut appear to disagree. They are not the only ones. R. Yaakov Perlow, the Novominsker Rebbi, wrote a long article where he also takes issue with Eliakh's book. He also claims that R. Eliakh should have left out the details of the controversy.

It would appear that there is a fundamental controversy as to whether or not one should lie regarding history. In fact, in the journal Ohr Yisrael, there was an article addressing this very point - whether one should lie to tell stories that create yirat shamyim. The author concludes "if the teacher is telling stories which are not true, but is doing so leshem shamyim, so long as he doesn't make a habit out of it, there is a place to be lenient in this matter, however, one should try to minimize this."

Interestingly, in the next volume the Admor from Slonim has a stinging rebuttal of the article. He starts by saying, "Our tradition is based upon truth . . . how terrible it is to inject lies into our tradition." He then explains such a view undermines our entire religion "whomever permits [one to lie] it is as if he is creating uncertainty in the truth of our entire tradition, which is based upon the passing from generation to generation. My teachers have taught that one should only accept truthful stories."

So it would appear that there is an ongoing controversy, one which implicated the book HaGaon, with some arguing lying or covering up fundamental historical facts, is ok. While others claim this is totally unconscionable.

Sources: Olam haHassidut no. 88, Shevat 2002; 89, Adar 2002; 90, Nissan, 2002. Rabbi H. Oberlander, "HaIm Mutar l'Saper Ma'siyot shaninom amitim kedi l'orrer al yedi zeh l'Torah v'lyerat shaymim, Ohr Yisrael, 29 p. 121-123; R. Avrohom Weinberg (Admor M'Slonim Beni Brak), Letter, Ohr Yisrael, 30, 244. See also, Ari Zivotofsky, Perspectives on Truthfulness in the Jewish Tradition, Judaism 42:3 (Summer, 1993): 267-288. R. Yaakov Perlow, Yeshurun vol. 10 starting on page 831. Der Yid, Talumat Seftei Sheker haDovrot al Tzadik Atik, March 17, 2006. See also here for a discussion of the book. There are others that discuss this as well, and in R. Nathan Kamenetsky's introduction he quotes them. Further, as a helpful reader/movie buff has noted, I should have included R. Dr. Jacob J. Schacter's article on this topic available here.

↧

↧

Eliyahu Drinking from the Cup

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() I hope to have a few posts in the coming days discussing some of the artwork found in various haggdah. While for hundreds of years artwork played an integral part of the haggadah recently this has fell into disuse. While there are few notable exceptions to this, Raskin, Moss Haggadahs, this practice of richly illustrating the haggdah has been replaced with a focus on commentaries.

I hope to have a few posts in the coming days discussing some of the artwork found in various haggdah. While for hundreds of years artwork played an integral part of the haggadah recently this has fell into disuse. While there are few notable exceptions to this, Raskin, Moss Haggadahs, this practice of richly illustrating the haggdah has been replaced with a focus on commentaries.

One of the reasons, however, the practice of illustrating the haggadah, can be found in the discussion which sheds light on the custom of pretending or assuming that Eliyahu, who according to legend, visits each home on Pesach night.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

The last cup of wine poured is for Eliyahu. While originally this cup was not necessarily connected to Eliyahu, today it has become associated with him. The cup of Eliyahu is not mentioned until the 15th century. Various reasons are given. The Gra explains as there is a controversy whether one must drink 4 or 5 cups, a controversy which will be resolved only when Eliyahu comes. (Divrei Eliyahu, Parshat Va'arah p. 35). The earliest source to discuss the cup, R. Zeligman Benga (student of Mahril), says that the custom to pour a cup for Eliyahu is as the night of Passover is an auspicious night for redemption, we await Eliyahu's coming and therefore we need a cup for him.

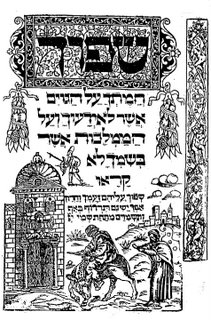

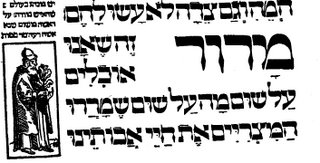

A rather interesting custom sprang up in connection with Eliyahu's visit on Pesach night. R. Jousep Schammes (1604-1678), records that the custom in Worms was to draw depictions of Eliyahu and the Messiah in order to bring to life the belief in these figures. As you can see from the pictures on the side, this was common in the Haggadah. The first picture is a depiction of Messiah on his donkey. This was originally depicted in smaller format in the Prague 1526 haggadah, but in this edition, Mantua, 1560 is greatly enlarged. The second picture comes from the Venice 1629 hagaddah. As you can see it is again the Messiah coming in to Jerusalem, but note the prominence of the Dome of the Rock in the center.

In Frankfort they went one step further than just drawing Eliyahu and the Messiah. R. Yosef Jousep Hahn (1570-1637) says they used to hang a dummy who looked like Eliyahu or the Messiah behind the door. When they would open the door for Eliyahu the dummy would drop down and seem as if he had appeared. (He then goes on to record a long story of a dybuk who invaded the body of a women who questioned whether the Exodus happened.) It is worthwhile noting that not everyone was thrilled with these depictions. R. Yair Hayyim Bacharach (1639-1702) who became the Rabbi in Worms at the very end of his life, says these types of things only make a mockery of the seder.

However, we see from the above, that there was, at least among some, an effort to create a feeling that Eliyahu actually would visit the seder. Some did it through pictures, others through reenactments. Although today those have fallen to the wayside, it would seem the idea that Eliyahu actually drinks from the cup is a form of those methods.

Sources: Yerusalmi, Haggadah and History; Shmuel and Zev Safrai, Haggadah of the Sages, p 177-78. Minhagei Vermisai, p. פז; R. Y. Bacharach, Mekor Hayyim.

Clik here to view.

I hope to have a few posts in the coming days discussing some of the artwork found in various haggdah. While for hundreds of years artwork played an integral part of the haggadah recently this has fell into disuse. While there are few notable exceptions to this, Raskin, Moss Haggadahs, this practice of richly illustrating the haggdah has been replaced with a focus on commentaries.

I hope to have a few posts in the coming days discussing some of the artwork found in various haggdah. While for hundreds of years artwork played an integral part of the haggadah recently this has fell into disuse. While there are few notable exceptions to this, Raskin, Moss Haggadahs, this practice of richly illustrating the haggdah has been replaced with a focus on commentaries.One of the reasons, however, the practice of illustrating the haggadah, can be found in the discussion which sheds light on the custom of pretending or assuming that Eliyahu, who according to legend, visits each home on Pesach night.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The last cup of wine poured is for Eliyahu. While originally this cup was not necessarily connected to Eliyahu, today it has become associated with him. The cup of Eliyahu is not mentioned until the 15th century. Various reasons are given. The Gra explains as there is a controversy whether one must drink 4 or 5 cups, a controversy which will be resolved only when Eliyahu comes. (Divrei Eliyahu, Parshat Va'arah p. 35). The earliest source to discuss the cup, R. Zeligman Benga (student of Mahril), says that the custom to pour a cup for Eliyahu is as the night of Passover is an auspicious night for redemption, we await Eliyahu's coming and therefore we need a cup for him.

A rather interesting custom sprang up in connection with Eliyahu's visit on Pesach night. R. Jousep Schammes (1604-1678), records that the custom in Worms was to draw depictions of Eliyahu and the Messiah in order to bring to life the belief in these figures. As you can see from the pictures on the side, this was common in the Haggadah. The first picture is a depiction of Messiah on his donkey. This was originally depicted in smaller format in the Prague 1526 haggadah, but in this edition, Mantua, 1560 is greatly enlarged. The second picture comes from the Venice 1629 hagaddah. As you can see it is again the Messiah coming in to Jerusalem, but note the prominence of the Dome of the Rock in the center.

In Frankfort they went one step further than just drawing Eliyahu and the Messiah. R. Yosef Jousep Hahn (1570-1637) says they used to hang a dummy who looked like Eliyahu or the Messiah behind the door. When they would open the door for Eliyahu the dummy would drop down and seem as if he had appeared. (He then goes on to record a long story of a dybuk who invaded the body of a women who questioned whether the Exodus happened.) It is worthwhile noting that not everyone was thrilled with these depictions. R. Yair Hayyim Bacharach (1639-1702) who became the Rabbi in Worms at the very end of his life, says these types of things only make a mockery of the seder.

However, we see from the above, that there was, at least among some, an effort to create a feeling that Eliyahu actually would visit the seder. Some did it through pictures, others through reenactments. Although today those have fallen to the wayside, it would seem the idea that Eliyahu actually drinks from the cup is a form of those methods.

Sources: Yerusalmi, Haggadah and History; Shmuel and Zev Safrai, Haggadah of the Sages, p 177-78. Minhagei Vermisai, p. פז; R. Y. Bacharach, Mekor Hayyim.

↧

Prague 1526 Haggadah

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() The first fully illustrated haggadah was the Prague Image may be NSFW.

The first fully illustrated haggadah was the Prague Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() 1526 haggadah. This haggadah was reprinted in 1977 by Mekor and is now available for everyone at the Jewish National University Library site here. (They have other important haggadas available for viewing including some of the earliest haggadas).

1526 haggadah. This haggadah was reprinted in 1977 by Mekor and is now available for everyone at the Jewish National University Library site here. (They have other important haggadas available for viewing including some of the earliest haggadas).

The Prague haggadah is filled with fascinating and important illustrations. As we have seen previously, the Prague haggadah contained nudes, which when appropriated later were removed. This included in the haggadah context as well as in other works.

Aside from these illustrations, there is an illustration of Abraham when God takes him "from the other side of the river." In the Prague haggadah we have Abraham in a row boat. However, when this was appropriated in the Mantau, 1560 haggadah, the row boat was changed into a gondola.

Also, this haggadah contains brief comments or instructions as well as the text of the haggadah. There are two which beImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() ar mention. The first is the passage underneath the Tam - simple - son. Typically, the simple son is understood to be less than stellar. However, in this haggadah, the verse תמים תהיה עם ה' אלקך (One should be simple with God) (Devarim 18:13). As this verse is claiming this simplemindedness is a good attribute, this seems to indicate that the simplemindedness of the son is something positive.

ar mention. The first is the passage underneath the Tam - simple - son. Typically, the simple son is understood to be less than stellar. However, in this haggadah, the verse תמים תהיה עם ה' אלקך (One should be simple with God) (Devarim 18:13). As this verse is claiming this simplemindedness is a good attribute, this seems to indicate that the simplemindedness of the son is something positive.

The second passage comes in the form of an instruction. In the margin at the mention of marror the bitter herb, is the following "It is a universal custom to point at one's wife [at the mention of marror] as the verse says 'I have found the woman worse [more bitter] than death. (Kohelet 7:26)'"

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

The first fully illustrated haggadah was the Prague Image may be NSFW.

The first fully illustrated haggadah was the Prague Image may be NSFW.Clik here to view.

1526 haggadah. This haggadah was reprinted in 1977 by Mekor and is now available for everyone at the Jewish National University Library site here. (They have other important haggadas available for viewing including some of the earliest haggadas).

1526 haggadah. This haggadah was reprinted in 1977 by Mekor and is now available for everyone at the Jewish National University Library site here. (They have other important haggadas available for viewing including some of the earliest haggadas).The Prague haggadah is filled with fascinating and important illustrations. As we have seen previously, the Prague haggadah contained nudes, which when appropriated later were removed. This included in the haggadah context as well as in other works.

Aside from these illustrations, there is an illustration of Abraham when God takes him "from the other side of the river." In the Prague haggadah we have Abraham in a row boat. However, when this was appropriated in the Mantau, 1560 haggadah, the row boat was changed into a gondola.

Also, this haggadah contains brief comments or instructions as well as the text of the haggadah. There are two which beImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

ar mention. The first is the passage underneath the Tam - simple - son. Typically, the simple son is understood to be less than stellar. However, in this haggadah, the verse תמים תהיה עם ה' אלקך (One should be simple with God) (Devarim 18:13). As this verse is claiming this simplemindedness is a good attribute, this seems to indicate that the simplemindedness of the son is something positive.

ar mention. The first is the passage underneath the Tam - simple - son. Typically, the simple son is understood to be less than stellar. However, in this haggadah, the verse תמים תהיה עם ה' אלקך (One should be simple with God) (Devarim 18:13). As this verse is claiming this simplemindedness is a good attribute, this seems to indicate that the simplemindedness of the son is something positive.The second passage comes in the form of an instruction. In the margin at the mention of marror the bitter herb, is the following "It is a universal custom to point at one's wife [at the mention of marror] as the verse says 'I have found the woman worse [more bitter] than death. (Kohelet 7:26)'"

↧

Pesach posts

Also, if you haven't already seen it Menachem Mendal has a very interesting post about using oat matzo for pessach. He also has a great post on another story assumed to be of Jewish origin which is not (the story of the two brothers and the temple mount).

Also one hopes that Mississippi Fred McDowell will post on his excellent site English Hebraica, on the early haggadas printed with English or in England.

Finally, although not directly related to pesach, although it would not be that hard to tie it in, there is a new Mishna Berura Yomi blog for all those wishing to devel deeper into this work.

↧

Pesach Shir HaShirim Contest

Two other Pesach issues.

First, as we are discussing haggadas, if people have favorites or others they feel are worthwhile letting others know about please comment.

Second, as this blog is ostensibly about seforim and over Pesach we read Shir HaShirim I figured we could have a contest. While others concentrate on more important things, Shir HaShirim, to my knowledge has the greatest concentration of names of seforim in any book in the bible. So the contest is - who can come up with the largest list? The longest list is that one which uses the most amount of words in Shir HaShirim and not just the most seforim. So if you have multiple books with the same title that only counts as one. I think we can also count journal titles unless people think that is unfair.

First, as we are discussing haggadas, if people have favorites or others they feel are worthwhile letting others know about please comment.

Second, as this blog is ostensibly about seforim and over Pesach we read Shir HaShirim I figured we could have a contest. While others concentrate on more important things, Shir HaShirim, to my knowledge has the greatest concentration of names of seforim in any book in the bible. So the contest is - who can come up with the largest list? The longest list is that one which uses the most amount of words in Shir HaShirim and not just the most seforim. So if you have multiple books with the same title that only counts as one. I think we can also count journal titles unless people think that is unfair.

↧

↧

Gettting Kabbalah Customs Wrong, Removing Teffilin on Hol HaMoad

On the Main Line had a discussion regarding whether one should or should not follow customs based upon kabbalah. He brought up the custom of removing teffilin on Rosh Hodesh "before Mussaf." However, what is facinating about this custom of removing the teffilin is that most people actually get it wrong. That is, according to just about everyone that discusses this one should not remove ones teffilin right before mussaf.

The first to address this custom in a meaningful manner was R. Azariah m'Fano, one the leading kabbalists of his day.

R. Mordechi Yaffo, in his Levush also says that one should remove them before the reading of the torah. R. Eliyahu Shapiro in his Eliyahu Rabba and Zuta quotes R. Fano and agrees that one should not remove them right before mussaf. R. Karo in Shulchan Orakh just states that one shouldn't wear them for mussaf but does not say when one should remove them. R. Moshe Isserles does the same. In fact, on Hol HaMo'ad, those who wear teffilin remove them not right before mussaf but instead before hallel.

So one may be asking themselves, well if everyone that disucsses when one should take them off says to do so much earlier than we do, how come no one does that now. And for that, we need to turn to R. Avroahom (hamechune Abeli) Gombiner in his Mogen Avrohom. The Mogen Avrohom cites a passage which is attributed to R. Issac Luria that one should wait to remove the teffilin until after the reading of the torah. Now, asute readers will realize that even according to this, one can still fullfill all the opinions (or close enough) and wait to remove the teffilin until after the torah reading but long before mussaf. However, again, most don't do this, instead they wait until right before mussaf, right at the time R. Fano, no lightweight said one is disrespecting God.

So we now turn to the another passage in the Magen Avraham for the answer. There is a custom to have the teffilin on for 4 kaddashim and 3 keddusot (kedusha in yotzer, kedusah in Shemoneh esreh, and the kedusah of u'va l'tzion). So the question becomes what does one have to do on Rosh Hodesh. Does one need to leave the teffilin on for those kaddashim or because of these other reasons, namely the mussaf can one ignore that requirement on Rosh Hodesh. The Mogen Avrohom says that Rosh Hodesh is different than Hol haMo'ad and on Rosh Hodesh one can not ignore that requirement and therefore one must keep the teffilin on until after the kaddish following u'va l'tzyion.

But here is the issue with the Mogen Avrohom, R. Yeshaya Horowitz (Shelah) holds that really this requirement is switched and one only need 3 kaddashim and 4 kedushot (he counts barakhu as the fourth). So according to him, one has already gotten their three kaddashim after the reading of the Torah.

So to recap, in order for one to require removal of the teffilin right before mussaf one needs to ignore R. Fano (and others who follow him), and ignore R. Horowitz as well.

[As an aside, R. David ben Levi in his Taz says that one need not remove his teffilin at all. R. Joseph Baer Soloveitchik held that if one doesn't have time to wrap them before begining mussaf one should follow the Taz and just say mussaf with them on.]

Sources and further reading: Shu't Rama M'Fano no. 108 (reprinted in Siddur R. Shabtai Sofer, vol. 2 p. 238-39; R. Mordechi Yaffo, Levush, Orakh Hayyim, no. 25 (at the end) and no. 423; R. E. Shapiro, Eliayhu Rabba, Zuta on the Levush; R. Y. Karo, Shulchan Orakh, no. 423:4; R. M. Isserlles Rama, 25:13; Shulchan Orakh Ari"zal, no. 423; R. A. (hamechune Abeli) Gombiner, Mogen Avrohom, no. 25:28; id. at 30; 423:6; R. Nerelanger, Yosef Omets, no. 696; R. J. Kierchheim, Minhagai Vermisia, p. קפג; R. B. Hamburger, Gedoli HaDorot 'al Mishmar Minhagi Ashkenaz, p. 102-03; R. Yom Tov Lippman Heller, Hilchot Teffilin, Ma'adeni Yom Tov. no. 74

The first to address this custom in a meaningful manner was R. Azariah m'Fano, one the leading kabbalists of his day.

This is what one should do if they want to properly remove their teffilin on Rosh Hodesh. One should remove the teffilin right after shemoneh esreh and one should not wait until after u'va l'tzyion like other days . . . it is proper to remove them before one reads from the torah the portion discussing the mussaf sacrifice . . . and if one removes them before hallel this is even better . . . u'va l'tzyion on the day of Rosh Hodesh is really part of the mussaf . . . and it is wholly improper to wait to remove the teffilin right before one is going to start mussaf as this is worse than Yeravam who removed his teffilin before the king (Sanhederin 101b), there he only removed them in front of an earthly king but one who waits to remove his teffilin until right before mussaf is doing so in front of God.Thus, R. Fano has two basic points. First, one should not wear teffilin for any portion of the prayers connected with Rosh Hodesh and therefore one should preferably remove them before hallel but at the very least before reading the Torah. Second, one should certianly not remove them right before starting mussaf as this is highly disrespectful to God.

R. Mordechi Yaffo, in his Levush also says that one should remove them before the reading of the torah. R. Eliyahu Shapiro in his Eliyahu Rabba and Zuta quotes R. Fano and agrees that one should not remove them right before mussaf. R. Karo in Shulchan Orakh just states that one shouldn't wear them for mussaf but does not say when one should remove them. R. Moshe Isserles does the same. In fact, on Hol HaMo'ad, those who wear teffilin remove them not right before mussaf but instead before hallel.

So one may be asking themselves, well if everyone that disucsses when one should take them off says to do so much earlier than we do, how come no one does that now. And for that, we need to turn to R. Avroahom (hamechune Abeli) Gombiner in his Mogen Avrohom. The Mogen Avrohom cites a passage which is attributed to R. Issac Luria that one should wait to remove the teffilin until after the reading of the torah. Now, asute readers will realize that even according to this, one can still fullfill all the opinions (or close enough) and wait to remove the teffilin until after the torah reading but long before mussaf. However, again, most don't do this, instead they wait until right before mussaf, right at the time R. Fano, no lightweight said one is disrespecting God.

So we now turn to the another passage in the Magen Avraham for the answer. There is a custom to have the teffilin on for 4 kaddashim and 3 keddusot (kedusha in yotzer, kedusah in Shemoneh esreh, and the kedusah of u'va l'tzion). So the question becomes what does one have to do on Rosh Hodesh. Does one need to leave the teffilin on for those kaddashim or because of these other reasons, namely the mussaf can one ignore that requirement on Rosh Hodesh. The Mogen Avrohom says that Rosh Hodesh is different than Hol haMo'ad and on Rosh Hodesh one can not ignore that requirement and therefore one must keep the teffilin on until after the kaddish following u'va l'tzyion.

But here is the issue with the Mogen Avrohom, R. Yeshaya Horowitz (Shelah) holds that really this requirement is switched and one only need 3 kaddashim and 4 kedushot (he counts barakhu as the fourth). So according to him, one has already gotten their three kaddashim after the reading of the Torah.

So to recap, in order for one to require removal of the teffilin right before mussaf one needs to ignore R. Fano (and others who follow him), and ignore R. Horowitz as well.

[As an aside, R. David ben Levi in his Taz says that one need not remove his teffilin at all. R. Joseph Baer Soloveitchik held that if one doesn't have time to wrap them before begining mussaf one should follow the Taz and just say mussaf with them on.]

Sources and further reading: Shu't Rama M'Fano no. 108 (reprinted in Siddur R. Shabtai Sofer, vol. 2 p. 238-39; R. Mordechi Yaffo, Levush, Orakh Hayyim, no. 25 (at the end) and no. 423; R. E. Shapiro, Eliayhu Rabba, Zuta on the Levush; R. Y. Karo, Shulchan Orakh, no. 423:4; R. M. Isserlles Rama, 25:13; Shulchan Orakh Ari"zal, no. 423; R. A. (hamechune Abeli) Gombiner, Mogen Avrohom, no. 25:28; id. at 30; 423:6; R. Nerelanger, Yosef Omets, no. 696; R. J. Kierchheim, Minhagai Vermisia, p. קפג; R. B. Hamburger, Gedoli HaDorot 'al Mishmar Minhagi Ashkenaz, p. 102-03; R. Yom Tov Lippman Heller, Hilchot Teffilin, Ma'adeni Yom Tov. no. 74

↧

Az Yashir, Another Kabalah Custom Gone Wrong?

One of the most common and troublesome customs based upon kabalah is the addition of verses and targum to אז ישיר.

Everyday, at the end of pesuki de’zimra we recite az yashir. However, we for one, don’t start at the beginning of the shira. The beginning is at the verse that starts ויהי באשמורות הבוקר we begin at the אז ישיר. Secondly, we don’t end at the end of the shira either. Instead, we add either 4 or 6 verses at the end.

The threshold question is why was this change effected? Rashi, R. Shlomo Yitzhaki (1040-1105) in his Sefer haPardes (p. 321) explains, “Whenever we finish anything we end by reciting the verse twice [the end of tehillim, for example] for this reason we double the verse of ה' ימלוך the reason being that really the entire parsha of the shira that is, from ויהי באשמורות הבקר has 18 mentions of gods name. Every name has 4 letters thus forming the 72 letter name of god. The רשאונים, the early ones, enacted that we recite the shira everyday to remember this great miracle . However, we only recite the important or ikar portion thus we start from az yashir. We are therefore lacking 4 mentions of gods name. Therefore we repeat the verse twice and add the four verses afterwards. The last verse’s mention of God’s name does not count as it is future tense.” Thus, according to this passage, we now understand why it is we add the four verses at the end and repeat the verse and why we left out the first four verses. There are many other rishonim that offer similar explanations for this.[1]

Importantly, according to Rashi, the end of the Shira is at ה' ימלוך thus he repeats that verse. It is also clear that he did not say the verse that follows, כי בא סוס as a) he would not have repeated ה' ימלוך as it would not have been the end and b) because there is a mention of God’s name in that verse and thus we would have too many mentions and therefore we lose the numerology as we do not get the 72 letter name.

The many רשונים follow this understand and thus end the שירה and the daily recitation of אז ישיר at ה' ימלוך. In fact, early Ashkenazi Siddurim all end at ה' ימלוך. For example, the earliest printed siddur in Prague, 1513 does that. As does the סידור of R. Shabbti Sofer, first published in the mid-16th century, who was considered the סידור for his time, has the same reading.[2] The Rama, R. Moshe Isserles (1525-1572) in his מפה also cites the custom of repeating ה' ימלוך. Thus, up until the late 16th century we were only repeating ה' ימלוך and not saying כי בא. However, two people changed that. The first was the ארי"זל and the second was R. Yakkov Emden. The R. Avrahom Gombiner (1635-1682), in his commentary the מגן אברהם, (who cites numerous customs from the ארי), on the comments of the רמ"א previously mentioned, states that the ארי said the verse of כי בא after he repeated ה' ימלוך. R. Gombiner does not offer any explanation as to why theארי did so. However, R. Shmuel Kelin (1720-1806), in his מחצית השקל a super-commentary on the מגן אברהם, does offer an explanation. Before we look at his explanation we need to look at one other source for proper background.

The רמב"ן in his commentary on the Torah on the verse of כי בא, notes that although some hold that כי בא is part of the שירה he holds it is not.[3] Some may be questioning why this all matters. However, it is actually quite important. The rule is that in order for a ספר תורה to be כשר the שירה portion must be written in a specific manner. That is called ריח על גבי לבינה or as brickwork. One writes words then leaves a space and then directly underneath that space one writes the next line and so forth. Thus, according to Rashi, and those other cited by רמב"ן one cannot write the verse of כי בא in the שירה format. And according to רמב"ן one MUST write it in the שירה format.

It would appear that in deciding whether to say or not to say כי בא would depend on how our ספר תורה is written.

Getting back to the מחיצת השקל, he argues this very point. He states that the reason that the מגן אברהם and the ארי said to recite כי בא is for the sake of consistency as in our ספרי תורה we include it in the שירה4 However, there is a difficulty with this position or understanding of both the מגן אברהם and the ארי. As both are still advocating repeating ה' ימלוך but also saying כי בא which as we discussed disrupts the numerology and also, if you include כי בא, it makes little sense in repeating ה' ימלוך as it is no longer the end. Because of these questions some commentators note that R. Hayyim Yosef David Azulai (HIDA), the well-known bibliographer, stated that many statements attributed to the ארי are not actually from the ארי. These commentators claim that this is one of those statements that can not be relied upon.[5]

R. Yakov Emden (1698-1776) published his own edition of the siddur. This siddur included both a commentary and notes on the נוסח. 6 He had many alteration in the נוסח. However, his commentary became very popular and was reprinted numerous times. But in these reprints instead of using his נוסח they would put his commentary and notes on the bottom of a regular סידור 7 Thus, one could read in the bottom “don’t say such and such” and on the top you would have that very thing. In regards to the אז ישיר issue, R. Emden notes that his father, the חכם צבי, only said ה' ימלוך once and he included כי בא as because that is how it appears in our תורה. This, of course, works with the numerology, the מסורה, and the correct ending of the שירה. [In the new edition of R. Emden’s siddur which was supposed to utilize his נוסח and correct all the years of neglect, does not correct his error, nor many others. Instead it includes the double recitation and the תרגום and כי בא.]

In truth, it was not clear how we should write our תורה. For instance, the noted Mesora scholar and משומד– Jewish convert to Christianity, Christian David Ginsburg in his edition of the Tanach which is based upon over 70 manuscripts and 19 of the earliest printed editions does not include כי בא. In fact, numerous manuscripts, mainly of Italian or Sefardic origin, which as a side note are generally not considered מידויק , have only up to ה' ימלוך. For us, however, the Rambam includes כי בא in the שירה. Furthermore, the oldest complete and מדויק manuscript, the Leningrad Codex which is very similar to the Allepo Codex which the Rambam based his תורה on has כי בא as part of the שירה.8

For us, as is apparent by looking at any תורה today, we all include כי בא as part of the שירה thus, if we wanted to be consistent we would only say ה' ימלוך once and include כי בא.

In conclusion, the purpose of this was not for anyone to change what their current custom may be, as has been demonstrated there is authority for all practices. Instead, I think that this discussion is demonstrative of how complex and nuanced the תפילות are. If this one verse has so much behind it, there are treasure troves of complexity throughout the סידור.

Sources:

1] See e.g. from the school of Rashi, Machzor Vitri, 2004, p. 10; see also אבודרהם , אורחת חיים.

[2 See also סדור תפילות כמנחג אשכנז, Hanover, 1616; סדר תפילות לכל השנה כמנהג אשכנז ופולין, Frankfort 1691 available at http://www.jnul.huji.ac.il/dl/books/html/bk_all.htm

3] The Ibn Ezra and Rasbam hold that is part and the Ramban and Rashi hold it is not.

4] R. Kelin argues that if one wants to repeat any verse, according to the Ari, one should repeat the verse of כי בא as that is the end.

5] For more on the Ari’s writings and the transmission of those writings, see R. Hillel, כתבוני לדורות.

[6 This was published in 1745-1747.

7] This edition was known as סידור בית יעקב, the original was called עמודי שמים.

[8 Although, there is some discrepancy on this point in the manuscripts of the Rambam. That is, the manuscripts mainly from אשכנז do not include כי בא which would be in agreement with Rashi and the Ramban. However, many of the Rambam’s manuscripts do include כי בא, especially of note is the signed copy of the יד which includes it. See Jordan Penkower, עדות חדש בנוסח כתר ארם צובא chapter 3.

Everyday, at the end of pesuki de’zimra we recite az yashir. However, we for one, don’t start at the beginning of the shira. The beginning is at the verse that starts ויהי באשמורות הבוקר we begin at the אז ישיר. Secondly, we don’t end at the end of the shira either. Instead, we add either 4 or 6 verses at the end.

The threshold question is why was this change effected? Rashi, R. Shlomo Yitzhaki (1040-1105) in his Sefer haPardes (p. 321) explains, “Whenever we finish anything we end by reciting the verse twice [the end of tehillim, for example] for this reason we double the verse of ה' ימלוך the reason being that really the entire parsha of the shira that is, from ויהי באשמורות הבקר has 18 mentions of gods name. Every name has 4 letters thus forming the 72 letter name of god. The רשאונים, the early ones, enacted that we recite the shira everyday to remember this great miracle . However, we only recite the important or ikar portion thus we start from az yashir. We are therefore lacking 4 mentions of gods name. Therefore we repeat the verse twice and add the four verses afterwards. The last verse’s mention of God’s name does not count as it is future tense.” Thus, according to this passage, we now understand why it is we add the four verses at the end and repeat the verse and why we left out the first four verses. There are many other rishonim that offer similar explanations for this.[1]

Importantly, according to Rashi, the end of the Shira is at ה' ימלוך thus he repeats that verse. It is also clear that he did not say the verse that follows, כי בא סוס as a) he would not have repeated ה' ימלוך as it would not have been the end and b) because there is a mention of God’s name in that verse and thus we would have too many mentions and therefore we lose the numerology as we do not get the 72 letter name.

The many רשונים follow this understand and thus end the שירה and the daily recitation of אז ישיר at ה' ימלוך. In fact, early Ashkenazi Siddurim all end at ה' ימלוך. For example, the earliest printed siddur in Prague, 1513 does that. As does the סידור of R. Shabbti Sofer, first published in the mid-16th century, who was considered the סידור for his time, has the same reading.[2] The Rama, R. Moshe Isserles (1525-1572) in his מפה also cites the custom of repeating ה' ימלוך. Thus, up until the late 16th century we were only repeating ה' ימלוך and not saying כי בא. However, two people changed that. The first was the ארי"זל and the second was R. Yakkov Emden. The R. Avrahom Gombiner (1635-1682), in his commentary the מגן אברהם, (who cites numerous customs from the ארי), on the comments of the רמ"א previously mentioned, states that the ארי said the verse of כי בא after he repeated ה' ימלוך. R. Gombiner does not offer any explanation as to why theארי did so. However, R. Shmuel Kelin (1720-1806), in his מחצית השקל a super-commentary on the מגן אברהם, does offer an explanation. Before we look at his explanation we need to look at one other source for proper background.

The רמב"ן in his commentary on the Torah on the verse of כי בא, notes that although some hold that כי בא is part of the שירה he holds it is not.[3] Some may be questioning why this all matters. However, it is actually quite important. The rule is that in order for a ספר תורה to be כשר the שירה portion must be written in a specific manner. That is called ריח על גבי לבינה or as brickwork. One writes words then leaves a space and then directly underneath that space one writes the next line and so forth. Thus, according to Rashi, and those other cited by רמב"ן one cannot write the verse of כי בא in the שירה format. And according to רמב"ן one MUST write it in the שירה format.

It would appear that in deciding whether to say or not to say כי בא would depend on how our ספר תורה is written.

Getting back to the מחיצת השקל, he argues this very point. He states that the reason that the מגן אברהם and the ארי said to recite כי בא is for the sake of consistency as in our ספרי תורה we include it in the שירה4 However, there is a difficulty with this position or understanding of both the מגן אברהם and the ארי. As both are still advocating repeating ה' ימלוך but also saying כי בא which as we discussed disrupts the numerology and also, if you include כי בא, it makes little sense in repeating ה' ימלוך as it is no longer the end. Because of these questions some commentators note that R. Hayyim Yosef David Azulai (HIDA), the well-known bibliographer, stated that many statements attributed to the ארי are not actually from the ארי. These commentators claim that this is one of those statements that can not be relied upon.[5]

R. Yakov Emden (1698-1776) published his own edition of the siddur. This siddur included both a commentary and notes on the נוסח. 6 He had many alteration in the נוסח. However, his commentary became very popular and was reprinted numerous times. But in these reprints instead of using his נוסח they would put his commentary and notes on the bottom of a regular סידור 7 Thus, one could read in the bottom “don’t say such and such” and on the top you would have that very thing. In regards to the אז ישיר issue, R. Emden notes that his father, the חכם צבי, only said ה' ימלוך once and he included כי בא as because that is how it appears in our תורה. This, of course, works with the numerology, the מסורה, and the correct ending of the שירה. [In the new edition of R. Emden’s siddur which was supposed to utilize his נוסח and correct all the years of neglect, does not correct his error, nor many others. Instead it includes the double recitation and the תרגום and כי בא.]

In truth, it was not clear how we should write our תורה. For instance, the noted Mesora scholar and משומד– Jewish convert to Christianity, Christian David Ginsburg in his edition of the Tanach which is based upon over 70 manuscripts and 19 of the earliest printed editions does not include כי בא. In fact, numerous manuscripts, mainly of Italian or Sefardic origin, which as a side note are generally not considered מידויק , have only up to ה' ימלוך. For us, however, the Rambam includes כי בא in the שירה. Furthermore, the oldest complete and מדויק manuscript, the Leningrad Codex which is very similar to the Allepo Codex which the Rambam based his תורה on has כי בא as part of the שירה.8

For us, as is apparent by looking at any תורה today, we all include כי בא as part of the שירה thus, if we wanted to be consistent we would only say ה' ימלוך once and include כי בא.

In conclusion, the purpose of this was not for anyone to change what their current custom may be, as has been demonstrated there is authority for all practices. Instead, I think that this discussion is demonstrative of how complex and nuanced the תפילות are. If this one verse has so much behind it, there are treasure troves of complexity throughout the סידור.

Sources:

1] See e.g. from the school of Rashi, Machzor Vitri, 2004, p. 10; see also אבודרהם , אורחת חיים.

[2 See also סדור תפילות כמנחג אשכנז, Hanover, 1616; סדר תפילות לכל השנה כמנהג אשכנז ופולין, Frankfort 1691 available at http://www.jnul.huji.ac.il/dl/books/html/bk_all.htm

3] The Ibn Ezra and Rasbam hold that is part and the Ramban and Rashi hold it is not.

4] R. Kelin argues that if one wants to repeat any verse, according to the Ari, one should repeat the verse of כי בא as that is the end.

5] For more on the Ari’s writings and the transmission of those writings, see R. Hillel, כתבוני לדורות.

[6 This was published in 1745-1747.

7] This edition was known as סידור בית יעקב, the original was called עמודי שמים.

[8 Although, there is some discrepancy on this point in the manuscripts of the Rambam. That is, the manuscripts mainly from אשכנז do not include כי בא which would be in agreement with Rashi and the Ramban. However, many of the Rambam’s manuscripts do include כי בא, especially of note is the signed copy of the יד which includes it. See Jordan Penkower, עדות חדש בנוסח כתר ארם צובא chapter 3.

↧

Separate Beds More on Illustrated Haggadot

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() As part of the hagadah there is an extensive discussion where various verses are discussed in depth. One of the verses, Devarim 26:7, says that "God heard our pain" (וירא את ענינו), this is interpreted in the hagadah as refraining from martial relations. In the Venice 1629 edition of the hagadah this is illustrated by having husband and wife sleeping in separate beds.

As part of the hagadah there is an extensive discussion where various verses are discussed in depth. One of the verses, Devarim 26:7, says that "God heard our pain" (וירא את ענינו), this is interpreted in the hagadah as refraining from martial relations. In the Venice 1629 edition of the hagadah this is illustrated by having husband and wife sleeping in separate beds.

[As you can also see, for some reason the text of this edition has two yuds in the word ענינו I don't know why.]

Also, you can see in the top left hand corner of the illustration (click on the picture for a more detailed view) a lamp is lit as well. I assume this was also to show the lack of marital relations. The law on Yom Kippur is that one needs to have a light on, according to one understanding this is so one will not come to have relations with ones wife. Perhaps this was used here for the same effect. This understanding is bolstered by the fact the Talmud in Yoma learns the prohabition against marital relations on Yom Kippur from the Eygptian slavery. (Yoma, 74b)

According to one scholar, Israel Yuval, this understanding of the verse is polemical in nature. He explains that when the Jews were prohibited from martial relations this was "pain" as this "counteracts the claim of Jesus' miraculous birth." If one could have a child born through miraculous means, then it would mitigate the effect of abstinence. Consequently, we are emphasizing the Jewish view is that such abstinence is harmful.

[However, some have questioned Yuval's emphasis on finding Christological elements in the hagadah.]

Sources: Yerushalmi, Haggadah and History, plate 50; Joshua Kulp, The Origins of the Seder and Haggadah, Currents in Biblical Research, 4.1(2005) 109-134 (discussing Yuval and summarizing the state of the current literature); Safrai and Safrai, Haggadah of the Sages, 136-138.

Clik here to view.

As part of the hagadah there is an extensive discussion where various verses are discussed in depth. One of the verses, Devarim 26:7, says that "God heard our pain" (וירא את ענינו), this is interpreted in the hagadah as refraining from martial relations. In the Venice 1629 edition of the hagadah this is illustrated by having husband and wife sleeping in separate beds.

As part of the hagadah there is an extensive discussion where various verses are discussed in depth. One of the verses, Devarim 26:7, says that "God heard our pain" (וירא את ענינו), this is interpreted in the hagadah as refraining from martial relations. In the Venice 1629 edition of the hagadah this is illustrated by having husband and wife sleeping in separate beds.[As you can also see, for some reason the text of this edition has two yuds in the word ענינו I don't know why.]

Also, you can see in the top left hand corner of the illustration (click on the picture for a more detailed view) a lamp is lit as well. I assume this was also to show the lack of marital relations. The law on Yom Kippur is that one needs to have a light on, according to one understanding this is so one will not come to have relations with ones wife. Perhaps this was used here for the same effect. This understanding is bolstered by the fact the Talmud in Yoma learns the prohabition against marital relations on Yom Kippur from the Eygptian slavery. (Yoma, 74b)

According to one scholar, Israel Yuval, this understanding of the verse is polemical in nature. He explains that when the Jews were prohibited from martial relations this was "pain" as this "counteracts the claim of Jesus' miraculous birth." If one could have a child born through miraculous means, then it would mitigate the effect of abstinence. Consequently, we are emphasizing the Jewish view is that such abstinence is harmful.

[However, some have questioned Yuval's emphasis on finding Christological elements in the hagadah.]

Sources: Yerushalmi, Haggadah and History, plate 50; Joshua Kulp, The Origins of the Seder and Haggadah, Currents in Biblical Research, 4.1(2005) 109-134 (discussing Yuval and summarizing the state of the current literature); Safrai and Safrai, Haggadah of the Sages, 136-138.

↧

Review of Reckless Rites

While it is a bit out of season, I wanted to review Elliott Horowitz's new book Reckless Rites. In this book, subtitled "Purim and the Legacy of Jewish Violence," everything is viewed through the prism of the violence inflicted by the Jews upon their enemies at the end of Esther.