Rabbis and Communism

By

Marc B. Shapiro

I had intended my newest post to be on the Rav’s famous essay “Confrontation,” but I recently received the latest issue of Tradition with Rabbi Yitzchak Blau’s article “Rabbinic Responses to Communism,” so let me make a few comments about it. First, I must say that it is a good read, like all of Blau’s writing, and I was impressed with the range of topics he attempts to tackle. My only suggestion for improvement would have been to examine the larger context of Jewish communist anti-clerical sentiment, which made it very hard for the rabbis to be sympathetic to communism.

Yet this anti-clerical feeling did not arise in a vacuum. Quite apart from the traditional Marxist aversion to religion, the rabbis, like their non-Jewish religious counterparts, were generally aligned with the aristocracy, who paid their salary and took their sons as marriage partners for their daughters. The rabbis were thus seen as standing in the way of economic justice. In fact, there has been a long plutocratic tradition in the Jewish world, which meant complete disenfranchisement of the poor from all communal decisions. I don’t know of any Jewish community in history where people who could not afford to pay taxes were given communal voting rights. (This would be the modern equivalent of not giving welfare recipients the right to vote – wouldn’t the Republicans love to make this the law of the land!)

R. Samuel de Medina goes so far as to argue that the wealthy are qualitatively superior to the poor, citing in support of this horrible notion Eccl. 7:12: “For wisdom is a defense, even as money is a defense.” For him, money and wisdom are two sides of the same coin. [1] He also gives another proof to support his pro-wealth point of view. Gen. 41:56 states: “And the famine was over all the face of the earth (פני הארץ).” Upon this the Midrash comments that the face of the earth refers to the rich people (Tanhuma, ad loc.). From this we see, says de Medina, that the rich are at the head of the community and everyone else in the rear, not a position from which one leads.[2] As he puts it (and note how the poor and the ignorant are treated as one group):

Accepting the will of the majority, when that majority is composed of ignorant men, could lead to a perversion of justice. For if there were one hundred men in a city, ten of whom were wealthy, respected men, and ninety of whom were poor, and the ninety wanted to appoint a leader approved by them, would the ten prominent men have to submit to him regardless of who he was? Heaven forbid, this is not the accepted way (“the way of pleasantness”).[3]

None of this means that de Medina was insensitive to the needs of the poor. This was not the case at all, and he has a responsum in which he requires people to contribute to the building of houses that will be used, among other things, for poor visitors to spend the night.[4] Yet we see in him a sense of paternalism that was common in traditional societies all over the world, and was one of the factors which convinced the lower class that it was time to take matters into their own hands.[5]

When dealing with anti-clericalism in Russia, we must also not forget the masses’ long memory of how some (many?, most?) rabbis were silent during the era of the chappers. This was when children were grabbed for 25 years of military service in the Cantonists, often never again to see their parents and usually succumbing to incessant pressure (including torture) to be baptized. Yet it wasn’t the children of the rich or the rabbis who were taken, but the poor children. Jacob Lifshitz’ defense of the way the Jewish community dealt with the Cantonist tragedy – which he regards as worse than even the destruction of the Temple![6] – and his insistence that no one can judge the community leaders unless they themselves had been in such a difficult circumstance, is something we must bear in mind.[7] Yet all such ex post facto justifications would have no impact on the outlook of those that actually suffered during the Cantonist era, and it is no wonder that many of the common people would not regard the rabbis in a sympathetic light. The rabbis were certainly able to come up with a justification why their sons, the future Torah scholars, should not be taken to the army, just as they continue to make this argument. Yet this would only serve to show the masses that some children’s blood was indeed redder than others.[8]

In his memoir of this era, Yehudah Leib Levin wrote:

"I was relatively calm and personally did not fear the chappers, because my father was an important landlord, distinguished in Torah and highly regarded by everyone. My mother was the daughter of the most famous tzaddik (righteous person) of his generation, Rabbi Moshe Kabrina’at. And I, I was one of the “good children,” a prodigy the likes of whom were not touched by the hand of the masses. Free both of fear and of schoolwork, because the teachers and pupils had all gone into hiding and the chedarim [schools] were closed, I wandered daily around the city streets seeing the little “Russians,” and my heart burst when I realized they were in the hands of non-Jews, who forced them to eat pork – oh dear me!"[9]

Elyakum Zunser was seized when he was away from his hometown. Many years later he wrote:Many private individuals engaged in this traffic, seizing young children and selling them to the Kahal “bosses.” Reminiscent of the sale of Joseph by his own brothers, these betrayals occurred daily. Lesser rabbis of small towns assented to such transactions, rationalizing that it was more “pious” to save the children of their own towns than to concern themselves with the fate of strangers.

Though many important rabbis wept at these outrages, most dared not protest. They were afraid of the consequences if the Jewish community would defy the Tsar’s quota. The rabbis held their positions at the discretion of the Kahal leaders and feared the consequences of displeasing them. They were afraid to be denounced to government officials and exiled to Siberia.[10]

Michael Stanislawski notes that in one community the communal leaders wanted to grab a poor tailor since he wasn’t observant, but the local rabbi forbid it. Stanislawski also tells us that in Vilna the communal leaders had their sights on a larger prize.

[T]he traditionalist kahal authorities later attempted to forestall the opening of the government-sponsored rabbinical seminaries by drafting the sons of several of its proposed teachers, but this was discovered by the local administration and forbidden.[11]

He also quotes the Hebrew writer Y. L. Katsenson, who describes his grandmother’s shock when she discovered that the chappers in her town were not Gentiles:

No, my child, to our great horror, all khappers were in fact Jews, Jews with beards and sidelocks. We Jews are accustomed to attacks, libels, and evil decrees from the non-Jews – such have happened from time to time immemorial, and such is our lot in Exile. In the past, there were Gentiles who held a cross in one hand and a knife in the other, and said: “Jew, kiss the cross or die,” and the Jews preferred death to apostasy. But now there come Jews, religious Jews, who capture children and send them off to apostasy. Such a punishment was not even listed in the Bible’s list of the most horrible curses. Jews spill the blood of their brothers, and God is silent, the rabbis are silent. . . .[12]

What is incredible is that after all the pressure to convert, some Cantonists remained Jewish. In fact – and here I mention something that I only learnt after my book on R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg was published – Weinberg’s grandfather was a Cantonist. His father was also a soldier in the post-Cantonist Czarist army.[13] In the book I mentioned that Weinberg’s family was undistinguished, yet if I was writing it now I would speak about how the two generations of army service signifies that this was in fact a very low-class family, and shows how significant Weinberg’s rise to fame was. As I pointed out, while in theory the yeshivot were equal-opportunity institutions, in reality the aristocratic element in them was generally well established and self-perpetuating.[14]

In a strong defense of the rabbis against the charge that they collaborated with the rich people in order to ensure that the poor were taken, R. Moses Solomon Kazarnov calls attention to all that the rabbis did to defend the children of the lower class.[15] But he acknowledges that the rabbis would hand over the non-religious kids, including their own![16] (While I have no doubt that the rabbis joined with the parnasim to hand over the non-religious youth, it strains imagination to believe that there were more than a few who did this with their own irreligious sons.) As Kazarnov puts it (51-52, in words that must cause loathing in any contemporary parent, and I would assume in virtually all parents even one hundred years ago):

והרבנים איפא כבנים נאמנים לתלמודם הורו למעשה את אשר מצאו כתוב להלכה, ותמיד הורו לא אך לאחרים, אך גם לעצמם, אם בניהם לא נהגו כשורה, לנדותם להבזותם ולתת גם את חלקם לטובים מהם; כמה אבות רבנים או חרדים גרידא הנך זוכר קורא יקר, אשר בניהם יצאו לתרבות רעה ואשר התפללו לה' תמיד כי יחמול ה' עליהם ויקח את בניהם אלה מהם, כמה מהם השתדלו בעצמם להשיג את בניהם שנתפקרו למען מסרם לצבא תחת יתר בניהם הרודים עם א-ל?

Talk about conditional love! I don’t even want to imagine what it did to the mental state of a child who knew that his father would hand him over to the Czar’s army if he decided that he no longer wanted to be Orthodox. Kazarnov continues:

ואם כן אפוא מי זה יאשימם על הוראתם למסור למלכות לעבודת הצבא את החטאים תחת הכשרים? . . . הלא לא עשו לבני העניים יותר מאשר עשו לבניהם המם. את הכשרים שמרו כבבת עינם, אם שלהם ואם של אחרים, ואת החוטאים מסרו לצבא אם מירכם יצאו או מירך זולתם! . . . במאכלות אסורות ובנבלות, זמה ורשע, בזדונות כאלה שמו החרדים את פניהם להמעיטם מקרב עמם, מקרב משפחתם ומקרב בני ביתם, ומה היא כל החרדה הזאת?

Concerning the general issue of the rabbis being allied with the wealthy, Dan Rabinowitz called my attention to what R. Judah Margaliot wrote in his Beit Middot:

Some of the leaders of Israel do not think of the glory of their Creator but only of their own. They employ all their power merely to terrorize the community. [He then elaborates on how they do this] . . . Do not think that one can turn for help to the great figures of the generation, to our rabbis, whose duty it is to be the protectors and defenders of the people. For they are in league with the oppressors, walk together with the powerful men and rulers of the city, become collaborators of every mischief-maker, give protection to every swindler. They exploit the rabbi’s title and authority for all kinds of evil deeds. Everything obtains the approval of the community rabbi. He who ought to be the guardian of righteousness and justice becomes the protector of robbers and bandits. The righteous judge joins the league of the swindlers. . . . . And these are our judges and lawgivers! Calmly they look on at the robberies and injustices that take place in the community and flatter the rich and powerful from whom every quarrel and plague come.[17]

Returning to the issue of poverty, which de Medina sees as a disqualifier for communal leadership, we can also find more positive evaluations of it. Nedarim 81a tells us not to neglect the children of the poor, for the Torah goes out from them. If you examine the commentaries on this passage you will certainly find those who point out that it is easier for a poor person to study Torah, as he does not have the same attachment to the material world as does the wealthy man, and it is this attachment that prevents one from focusing on Torah. I read these sources as designed to be encouraging. In other words, they are ex post facto judgments of the positive that can be found in poverty, so that people in this unfortunate state don’t think that all is lost.

Yet in the entire history of the Jewish people I don’t know of any source that says that it is good to be poor, and that this is something that one should strive for. In fact, the Talmud states that one who is poor is like one who is dead (Nedarim 64b), and puts poverty in the same category as childlessness, leprosy, and blindness, all things that we hope we never have to deal with. Similarly, R. Phineas b. Hama stated: ”Poverty in one's home is worse than fifty plagues” (Bava Batra 116a). In Eruvin 41b extreme poverty is listed as one of the three things that “deprive a man of his senses and of a knowledge of his Creator.”

The notion that it is harder for a rich person to get into heaven than to put a camel through the eye of a needle has never been a Jewish teaching, and Jews have regarded wealth as a blessing. It is a challenging blessing, but a blessing nonetheless.

Yet when questioned by those who pointed out how difficult poverty is for the kollel students in Israel, R. Aryeh Leib Steinman responded with what, to my knowledge, is a completely new approach, one which idealizes poverty in a manner not very different than the Christian notion of “Blessed be ye poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.” (Luke 6:20):

While everyone must distance themselves from unnecessary expenditures and luxuries just as they would be careful of fire, Bnei Torah have an especial obligation as the simple life is recommended for acquiring Torah, and they have it better if they live a life of simplicity and tsnius, and even poverty and want. It says: This is the way of Torah – eat bread with salt. But it is important to stress that what is necessary is strengthening emunoh and dedication to Torah. One should definitely not look for solutions that might cause avreichim to leave learning, G-d forbid.

I was asked if it would be a good idea to open offices for chareidi men in the large chareidi cities so that they could work in an appropriate atmosphere. It is obvious that the idea is a bad one though the intentions are good. The fact that the workplaces would be especially suited to the needs of chareidi men, and set up by chareidi people, might encourage people in difficult financial situations to leave learning. It is a spiritual stumbling block for the community at large. It would be terrible even if it would cause just one man to leave full-time learning. . . .

What are the effects of poverty? The answer is that it is better to be poor than to be rich, as Torah comes forth from the poor; they are the ones that become talmidei chachomim. The Jewish People has always undergone difficult trials. Historically, it's been the poor people who have maintained their commitment to Judaism, despite the difficulties. It was among the rich people that some failed to withstand the temptations and trials. They are the ones that lost their children and grandchildren to Torah. It was the poor who remained especially steadfast in their dedication.

I have personally witnessed, and history testifies, that in all of the places where people learned Torah in poverty, they were able to maintain the Mesorah. In the places where the people had a comfortable standard of living, their learning was not immune to the Haskalah's influences and many abandoned the Jewish and Torah way of life.[18]

Returning to Blau’s article, I was happy to see that he cited R. Jacob Emden who expressed admiration for shared property. I would just note that as with so many other issues in his writings, Emden had an alternate opinion as well, and here he comes out looking like his contemporary, Adam Smith. Emden explains how poverty is essential to a successful economic order. He notes that without the motivating factor of those who are in need – what Gordon Gekko would call “greed”[19] and what others will call “self-interest” – no economic progress will ever be made. If people are not able to improve their economic state, they will not take the risks that stand behind all new ideas and discoveries, which are precisely what keeps the economic engine of a society going. Communism, which took away the hope of personal gain, stifled all of this creativity.

Showing keen insight, Emden writes that if everyone had sufficient economic security, no one would travel on ships to far-away places and bring back the goods that are so important to people, no one would agree to do the back-breaking work required to build society’s great structures, and no one would take the time to come up with new inventions such as clocks and מחזות, which Azriel Schochet[20] suggests means glasses but I think telescopes is just as likely.

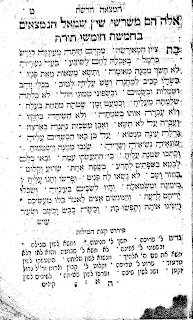

The passage appears in Birat Migdal Oz, 138b, but since the edition I have access to (on Otzar ha-Hokhmah) does not have page nos., I will cite it as it appears in Schochet, Im Hillufei Tekufot, 224-225:

והפלא מהשגחת הבורא הפרטית לתועלת עולמו ולהשלים תקנת בני אדם דרי תבל למלא חסרונם בהמצא בהם עניים ודלים. כי זולתם לא היתה הארץ נעבדת לתת יבולה ופריה, ולא היו מתגלים מחצבי הכסף והזהב ואבנים יקרות וסממני הרפואה ומיני הצבעים הנחפרים מן הארץ להודיע טובה ושבחה ושפעה הרב, לא תחסר כל בה. ואם היו כולם שבעים ומושפעים בשוה לא היה אחד מהם טורח להשיג דבר מן הדברים הנזכרים, ואצ"ל שלא היה שום אדם מסכים לרכוב אניות ולדרוך אניות להביא לחמו ממרחק ולמלא חסרון המדינות נעדרי התבואות והדברים היקרים וראשי בשמים והסמים הפשוטים, ולא היה מי מהם שירצה להעמיס על עצמו המלאכות הכבדות כבנית הבנינים הגדולים והיכלות תמלכים ומגדלים, ערים בצורות וחפירות הבורות והבארות, והיה העולם שמם. וכל שכן שלא היה אחד טורח בשכלו ובכח ידו להמציא תחבולות ואומניות נפלאות, כמו כלי השעות והמחזות והדומה להם מהאריגה והציורים ופתוחי חותם, והרבה מה שיארך זכרו, ולא היה ניכר שוע לפני דל, ובסיבת העוני ישיגו בני אדם כל הטובות הגדולות הרבות ההנה, והעני והחסר ישיג בהם די מחיתו והשלמת חסרונו ברצונו. מלבד מה שישיגו ע"י כך אורחות חיים כי יחלץ עני בעניו ע"י שנצרף בכור העוני, והעושר זוכה בו ומהנהו מנכסיו, מאיר עיני שניהם ה'.

I was also happy to see that Blau mentioned R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg’s views, although he overlooked Li-Frakim (2002 ed.), 578-582 and Kitvei ha-Rav Weinberg, vol. 2, 404-408,[21] the latter of which is devoted to Marx.

As can be expected, the rabbinic figures Blau surveys in his recent article in Tradition were no great fans of communism.[22] He writes: “My research failed to turn up a single Rabbi [!] of recognized stature who endorsed the communist program.”

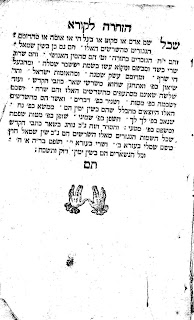

.יגעתי ומצאתי After the February 1917 Russian Revolution which brought Kerensky to power, the Orthodox formed a group called Masoret ve-Herut. It contained both Zionists and non-Zionists and was supposed to send a delegation to the All Russian Jewish Congress, which because of the Bolshevik revolution never took place. The group also envisioned itself becoming a real political power with the establishment of the new government. On the seventeenth of Tamuz, 1917, over fifty rabbis came to Moscow for discussions about this, including R. Avraham Dov Shapiro of Kovno, R. Abraham Aaron Burstein of Tavrig,[23] R. Isaac Rabinowitz of Ponovezh (R. Itzele), and R. Aaron Walkin of Pinsk. The Hafetz Hayyim sent greetings but was too ill to attend.

Since the masses did not have any property, one of the issues the new group would have to take a stand on was agrarian redistribution. With the Czar overthrown, it was possible to take not just his land but also the land that belonged to the wealthy princes, noblemen, and magnates and redistribute it, and this was certainly what the average person wanted. However, is this in accord with Jewish law? Can one confiscate another’s property? This was a subject of great controversy among the rabbis, and as can be imagined, many opposed this step. R. Itzele got up and, as recorded by R. Judah Leib Graubart,[24] said the following

החלק הפוליטי נחוץ, כי על ידו נמשוך את בני הנעורים והרחוב להסתדרותנו. גם הלא אנו רואים, כי כלל ישראל חפץ בו, בוודאי מאת ד' הייתה זאת. וכלל ישראל הוא גבוה ונעלה מגדולי התורה. ישראל אם אינם נביאים, בני נביאים הם.

In other words, if the Jewish people think that the concentration of land in the hands of a minority is unjust and should be redistributed, even if the rabbis claim that redistribution of the land is robbery, the opinion of the Jewish people overrides that of the rabbis.[25] Certainly, all would agree that R. Itzele is a rabbi of recognized stature.

Zalman Alpert called my attention to Jacob Mark’s discussion of R. Itzele in his Bi-Mehitzatam shel Gedolei ha-Dor, 116. Mark mentions that R. Itzele was greatly respected by the radicals (which included at least one of his own sons who was arrested in 1905 for revolutionary activities).[26] He was also very interested in socialism and carefully went through Marx’s Das Kapital. He was greatly impressed by Marx’s ideas, yet Mark notes that he commented: “I cannot agree with his positions, because they oppose the Torah law that protects private property.” I don’t deny that he said as much to Mark, but as we see from Graubart’s book, at the time of the Revolution he had a different perspective.[27] As to how, from a halakhic standpoint, he could have supported redistribution of wealth if the Torah protects private property, this is not a difficult problem. After all, as far as the Rabbis are concerned, governments have the right to engage in all sorts of taxation and redistribution of wealth.[28]

Eliezer Brodt called my attention to R. Moshe Shmuel Shapiro, Rabbi Moshe Shmuel ve-Doro (New York, 1964), 134-135, who tells an interesting story about R. Menashe of Ilya, one of the great students of the Vilna Gaon. (I can't say whether the story is apocryphal.) R. Menashe was greatly bothered by the terrible poverty in the Jewish community and came up with a revolutionary idea long before Marx. He proposed organizing a meeting of all the great rabbinic and lay leaders in the Jewish community, and their job would be to divide the Jewish wealth evenly. By doing so, the poverty problem would be solved and all would be equal. It is said that he turned to R. Hayyim of Volozhin and asked him to put his stature behind such a gathering. R. Hayyim replied that he is willing to be involved in one half of the program, i.e., the part where the poor receive the money, but the second part, in which the rich have to give up their money, he leaves to R. Menashe. Supposedly, R. Menashe understood from this answer that his plan had no hope.

R. Judah Leib Ashlag was another great rabbi who supported communism (see here ). It is very ironic that today Ashlag’s torch is carried by a few capitalist entrepreneurs, who have become very rich through the Kabbalah Centre.[29]

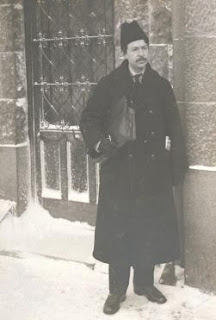

Isaac Steinberg, while not a rabbi, is a figure that should be mentioned. He was a leader of the Social Revolutionary Party and served as commissar for law in the first Soviet government. There is a lengthy article and picture of Steinberg in the Encyclopedia Judaica. Here is another picture of him.

Steinberg was also an Orthodox Jew. His ability to combine revolutionary views and Torah might be due to the influence of his teacher, the brilliant Rabbi Shlomo Barukh Rabinkow, who was himself “a convinced socialist and revolutionary.”[30]