In a recent

Mishpacha article [November 28, 2007, ‘Seforim Supplement’, p. 48] they quote Shlomo Biegeleisen, of Biegeleisen Books, as saying that “they receive sixty new seforim every single week!” The seforim market has exploded in the past few years and continues to grow daily. While it is impossible to keep up with everything that comes out we hope to keep the readers updated from time to time with some of the interesting things that are printed. This current list includes some of the many titles printed in the past few months.

Rishonim:

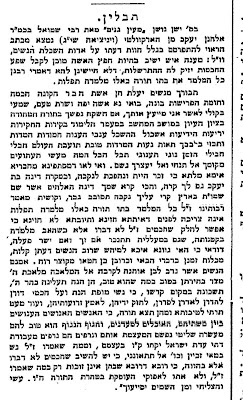

Mechon Haktav reprinted the

Magan Avos from R. Shlomo Duran, the Tashbatz (663 pp.). This work was first printed in 1785 and than again in a photo-mechanical edition by Mekor in the 1960’s. The plus of this recent edition is mainly the clarity of the print as the earlier edition is almost impossible to read. The editors of this edition did not, however, include notes of any sort on the sefer.

Sefer Al Esek Hatorah,

Shtei Dershos Lrabenu Harosh (Kiryat Sefer, 2007); 76 pp. [08-974-0626].

This volume is a small sefer written by the father of the Rosh on Limud Hatorah. It also includes two dershos of the Rosh. Parts of all this had been printed before in A. Freimann’s book on the Rosh. In this edition the editor rechecked the manuscripts and reprinting the whole thing all together. [For another work by this Mechon see

this prior post].

One of the dershos of the Rosh included in this work had been printed partially before by Professor Israel M. Ta-Shma in a few places [

Kiryat Sefer, then in the journal

MiGinzei L'taslume Kisvei Yad Ha'Ivriyim pp. 51- 52, and most recently in his

Knesset Mehakarim vol. two pp. 184 -186]. The second dersha included herein had been printed in its entirety by Y. Galinsky in his doctorate on the Tur,

Arbeh Turim V'safrus Halacha Shel Sefard b'Meha ha'arbah Aser (pp. 36-37, 74-75). In one of the dershos the Rosh gives strong mussar to the crowd for shying away to do certain Mitzvos such as lighting the Menorah in shul. There is a small historical argument between Professor Ta-Shma and Galinsky regarding the death of the Rashba (ibid.) based on the correct reading of a few words in the manuscript.

Mechon Yerushalim released their

Ramban on Chumash

Shemos see

here for their earlier volume.

Avkas Rochel (Ashdod, 2007); 103 pp. [08-853-1651]

The author of this work was Rabbenu Macir, a talmid of R. Yehudah, the son of the Rosh. This edition is a nice reprint of the original. It deals with topics such as Gan Eden, Gehenim, Olam Habah, Moshicah amongst many others.

Chumash:

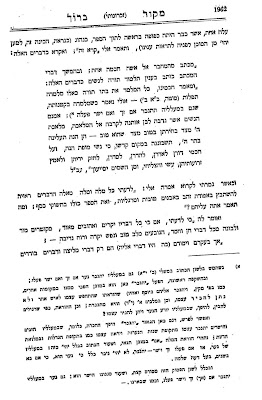

Maggid Meisharim (Jerusalem, 2007); 550 pgs, Ed. R. Y. Cohen [02 586-0457].

This edition is very helpful as it provides a parallel translation of the entire sefer from Aramaic into Hebrew. The editor also included paragraph highlights and many helpful notes on the sefer but hardly adequate for what this work actual deserves. [A while back there was a series of three articles by R. Yehuda Leib Kelers, in the

Tzefunous journal (1990-91), where he mentions that someone was actually starting such a project but as far as I am aware, nothing has come from it.]

Nachalei Afersomin (Jerusalem, 2007); 360 pp., [04- 864-0135].

This is a reprinted edition of the sefer from R. Rephael Balzam, a talmid of R. Meir Arik (and others). This work is on the Parsha, Mitzvos and Yomim Tovim. It includes an index and a nice short biography on the author. There are all kinds of styles of Torah in this work dealing with Kabbalah, Halacha and Machshaveh.

She'elot u-Teshuvot:

Shu"t Yeshuos Yakov was reprinted after not having been available for many years. This edition includes some nice new additions of Torah printed in various places. Hopefully there will be a full post on this Goan and his works shortly.

Shu"t Mateh Menashe from R. Menashe Statoh [By Hillel Statohn 368 pp. 718-382-0085].

The author was the Av beis Din of Tzafas over 150 years ago and was the father of R. Chaim author of the famous work

Eretz Hachaim. This work was in manuscript for all these years. In the second half of this sefer they include a fascinating work of the author called

Knessiah Leshem Shamaim, which had been printed before. The topic of this work is about an interesting custom that existed in many communities when someone was sick or childless. The custom was to do a whole elaborate process to appease the

shedim (evil spirits), a sort of offering to them (a

korbon of sorts). He discusses the entire topic explaining why it one is prohibited form doing such things. He deals with many topics such as the power of

shedim in general. This work includes the Teshuvous of many gedolim of the time amongst them R. Chaim Palagai.

Shu"t Sharei Tzion from R. Ben Zion Sternfeld was reprinted after not having been printed for a while. Besides for including R. Ben Zion's excellent teshuvos it includes many of his deroshos. This Goan is famous for giving the Chofetz Chaim haskamos on his

Mishana Berurah,

Shimiras Halaoshon and

Likitei Halachos. This edition includes the

Kuntres Darcha Shel Torah and

Kuntras Sharei Tzion on the topic of the importance of a proper education for one's children. This edition includes a small biography of the author. These two works were written in response to Maskilim whom complained about not learning dikduk etc. One point of great interest from these

Kuntreisim is the great importance and emphasis these Gedolim held of teaching Chumash properly to the children. They held that through the proper study of Chumash eventually the children will pick up Hebrew. Today, many school systems would do well to learn from these Gedolim to have proper methods to teach Chumash properly.

Shu"t Mishanat Sachir was reprinted. The author, R. Teichtel, was one of the biggest Rabbonim pre World War II in Hungary. As is very well known, originally R. Teichtel was a rabid anti-Zionist, however, later he completely changed his mind and eventually authored the incredible work called

Em Habonim Semaicha. He authored many teshuvos over the years and eventually printing one volume of the teshuvos. After his death, his son printed a massive volume of Shu"t thru Mechon Yerushalim. This work has been out of print for many years. It is fantastic in respects of both depth and Bikeius. The son printed another volume a few years later. This current edition includes the whole volume that was printed by Mechon Yerushalim and parts of the volume that was printed afterwards. The original volume that the author himself printed was not reprinted here. This edition also includes some pages of additions based on notes of R. Teichtel not printed before. Just to give one an interesting tidbit on this sefer:

About six years years ago a journal from Chabad in Budapest called

Tel Talpiyot (volume two) printed a few pages (pp. 42-55) of very interesting exchange of letters between R. Teichtel and his son R. Shlomo. This son went from Hungary to learn in Slabodkah Yeshivah. In the letters to his father he writes a few times how everyone in Slabodkah Yeshivah heard of his sefer and they enjoy it. He writes how many people asked him for a copy of the sefer but he only gave it to a few people amongst them the Divrei Yecheskel (see pp. 47, 48, 50).

Shas and Halacha:

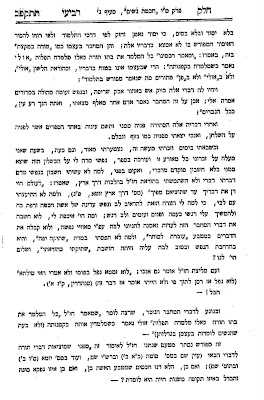

Mezareph Le'Chachmah (Jerusalem, 2007); 174 pp.

This particular work of R. Yosef Delmedigo (Yashar) has been the subject of much discussion for many centuries. Already R. Yehudah Aryeh Modena wrote that the views in this sefer are not the authors real opinions rather he was playing “games.” After that, Graetz and others and as recent as Barzilay have attempted to prove that Modena was correct. However, I feel after a careful reading of the sefer that it was

by no means a joke and this was the author’s real opinions. Recently, Professor David B. Ruderman has shown that Delmedigo did not intend this work to be a joke or game of some sort. Ruderman does so in his classic work

Jewish Thought and Scientific Discovery in Early Modern Europe (pp. 128-152) dealing with all the problems Geretz and others raised.

Mezareph Le'Chanchmah is full of interesting topics and information just to list a few: authorship of Zohar (52), Rashi (49) and Rambam's knowledge of Kabalah (37, 51), against R. Avraham Abulafiah (31), and when Nekudos are from (21-22). He has a whole section showing that there are no contradictions between Halacha and Kabblah. The Shach in Yoreh Deah quotes him in regard to eating meat after cheese (89:16).

This current edition is printed beautifully, however, they edited out all the notes of Delmedigo's student, R. Shmuel as well as some of the other stuff that were originally printed in this sefer. It is also lacking an index which would be very helpful with such a sefer enabling one to find all the treasures easily.

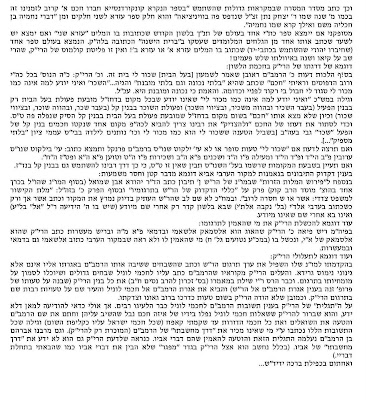

One original claim that I saw in the introduction of this edition and is recorded by many people and is in turn based on the Chida who states in R. Moshe Zechut's name that the Delmedigo's knowledge in kabbalah was not impressive based on specific things he writes in

Mezareph Le'Chachmah. The page from

Mezareph Le'Chachamah that lends credence to that opinion turns out that it was not from Delmedigo but instead from his talmid.

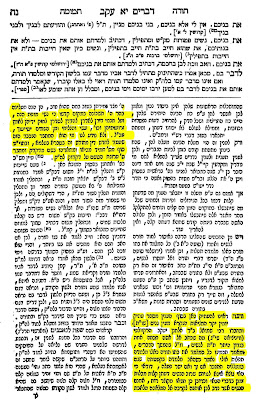

Kisvei Hagri (Jerusalem, 2007); 396 pp. [02 566-5240].

This a collection of the writings of R. Yaakov, Av Beis Din of Letichev. The author was born in 1730 and was rav there for many years. This was printed from manuscript for the first time by his descendants. The sefer has been waiting to be printed for nine generations. The editors put in lots of effort into this sefer giving you historical background. The sefer includes all kinds of genres, Chumash torah based on on old style pilpul, she'elot u-teshuvot, derush for all occasions (yom tovim etc.), hespedim, R. Yaakov's

tzavah and others. One of the many interesting things of interest in this sefer is a

Megilas Yuchsin that R. Yaakov wrote. The editors put in much effort to track down lots of material about it. Also included is a list of his seforim collection (useful for certain fields of interest see for example Zev Gris,

Hasefer K'Sochen Tarbus, pp. 65-72). Its unclear if the author was chassidish but he does quote from the Bal Shem Tov a few times.

Minhaghim and similar genre:

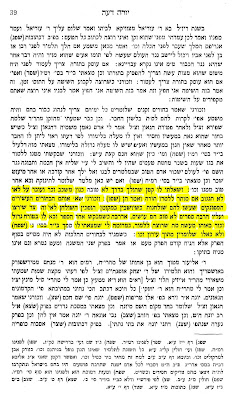

Chikrei Minhaghim (Cholon, 2007); 188 pp., [03- 556-3874]

This is a collection that focuses on Minhaghei Berlin gathered from many seforim including notes.

Orchos Hasofer (London, 2007); 173 pp.

This work is a beautiful collection of material about the Chasam Sofer gathered from a wide range of sources organized very nicely.

Bazel Hakodesh (Jerusalem, 2007); 334 pp.

This work is very interesting collection of material from R. B. Rakow collected together by his great-nephew. Topic ranges from chumash and halacha to stories he used to say over about various gedolim. Among the interesting discussions in this work are his opinions on learning and how to pasken, his connection with the Seridei Eish and his connection with R. Elyashiv resulting in getting R. Jonathan Sacks to take back what he wrote in one of his books [although the author does not mention R. Sacks by name] [See Marc B. Shaprio,

Of Books and Bans,

Edah Journal 3:2]. Another piece worthy of mention is his take on the Yeridos Hadoros question as it relates to learning.

Maseh Ish (Bnei Brak, 2007); 206 pp. Ed. R. Yabrov.

This is volume number seven of the on going series on the Chazon Ish. As with all such works there is lots of good stuff and some nonsense mixed in. This volume also includes a section on

shemitah.

Halichos Kodesh (Brooklyn, 2007); 316 pp.[718 336-8971, 718 972-4078]

This is a collection of the hanhagohs of the whole year of R. Yisroel Rotenberg, Av beis Din of Kossin. He was killed by the Nazis. The sefer is from the notes of a close talmid of his. Its an extremely in depth description, providing a day by day going thru the whole year how he acted in each situation its full of interesting things.

History:

Rishimos Teshuvos Rav Sherira Goan (New York, 2007); 119 pp., ed. R. Nosson Dovid Rabinowitz [917- 753-5178].

This sefer includes an excellent history of Rav Sherira Goan from the most updated sources in the academic world. It also includes listings of all the Teshuvos of Rav Sherira Goan including many that were mistakenly attributed to others.

Tohar Haloshon, ed. Rothschild (Jerusalem, 2007); 80 pp.

The theme of this sefer is to show that the historical acceptance of the Hebrew language – Ivrit, was, according to the author, a very tragic story. The author shows through the statements of Ben Yehudah and Y. Klausner how anti-Jewish they were. He also shows which terrible methods they used to make this the language spoken amongst Jews in Eretz Yisroel. The book, however, is not to objective, rather it is presented in a very

kannois way but all in all is still an interesting read to see a glimpse into that time period.

Olkieniki Radin Vilna (Jerusalem, 2007); 454 pgs, by R. Kalman Farber [02 571-1727, 03-731- 2149].

This is a diary of R. Farber of these places before World War Two and especially during the War. Among the interesting sections of this book are his accounts of his Rabaeim R. Naftoli Trop (known as

Granat) and the Chofetz Chaim.

Yosor Yasroni (Bnei Brak, 2007); 469 pp., by R. Yitzchak Gibralter [03-618-8360]

This is a book about Kovno, R. Gibralter home town. This is a very interesting book which gives one a very nice picture of Kovno before World War Two not a typical Artscroll like history.

Journals:

Heichel Ba'al Shem Tov, issue 21,189 pp.

There are two articles of interest in this latest issue one, an article from R. Chaim Rapoport on the minhag of Chasidim of seeing ones rebbe in general and other areas relating to this topic.

One of the sources on the topic which he brings is from a teshuvah of R Yakov Kahna in his

Shu"t Toldos Yakov (available

here) (no. 33, pp. 72-74, in particular). What is specifically interesting about this teshuvah is his discussion of the Gra and his stance against Chassidim. He basically writes that the Gra made a mistake - he was fooled by false witnesses! What is interesting about this is this R. Yakov Kahan grandfather was the Gra brother author of the

Maleos Hatorah! [I hope to return to this R. Yakov Kahana in a future post soon as his teshuvos are extremely interesting.]

Another point of interest, found in a different article, is a discussion of a grandson R. Chaim Volzhiner, Reb Eliyahu Zvi Soloveitchik, who became close with chassidus. The author references the extremely rare sefer by the Manhattan doctor, Arthur (Dov) Hyman, on this highly interesting personality.

Additions to earlier lists:

In an earlier

post on new seforim I mentioned a sefer from R Chaim Vital.

Here is some updated information on it as I have had more time to go thru it a bit. This sefer was printed by R. N. Levi. This sefer is based on the handwritten copy of R. Chaim Vital himself. This volume was part of the famous Musaef collection. The rumors on the street are that this sefer legally ended up in the hands of dealers who cut it up page by page and sold each page for $15,000. After all the pages of the sefer were sold it was printed in this beautiful edition. This actual work was actually six parts a few of the parts were printed many years ago including haskomos of R. Kook [vol. 2, printed in Jerusalem, 1906] and more recently by Mechon Ahavat Sholom. It appears that there is still a part not printed which was to be found in the Ger Rebbi's pre-World War II collection, which is currently still missing. As to the specific style of this sefer it is not heavy Kabbalah as there is much niglah in here. There are pieces of torah on everything – from chumash, aggdah gemaras and Mesectos Avos. Also included are many dershos which he said at chausunas, brisim and for hespedim. The dating of the sefer has been debated between R. Yakov Hillel and R. Manzur as to if this was before or after he learnt by the Arizal. Basically it seems that the bulk of the work was written before his learning with the Arizal and additions were added in by him throughout his lifetime.

The editor of this edition besides for presenting the work with nice layout and some sources include a basic history of R. Chaim Vital and his works. They consulted R. Y. Avivi who is a renowned Talmid Chacham and expert on Kabblah. Just to point out some minor comments on it. For some strange reason they quote a lot of material from M. Benayhu, but they can not properly write his name and instead refer to him as "the author of the Toldos HaAri" (for example see pp. 18, 19, 24, 31 and many more. They also can not properly write that he wrote the Sefer Yosef Bechrei which they also quote (pg 8, 14) or his Dor Eched baAretz (p. 72). Nor could they quote Avraham Yaari by name (pp. 45, 54) or Professor D. Tamar (pp. 48, 60) or Professor Tishbi (p. 67). What the problem in quoting these scholars name is beyond me. One more point in the end they deal with the sefer

Kabalah Maseios of R. Chaim Vital making no mention that parts have been printed already. I have elaborated earlier on this particular sefer in this post (

link). As an aside in the latest issue of

Mekabtzeul from Ahavat Sholom they printed some more pieces from this work.