by Marc B. Shaprio

[The footnote numbers reflects the fact this is a continuation of this earlier post.]

1. I was asked to expand a bit on how I know that R. Barukh Epstein’s story with Rayna Batya is contrived. In this story we see her great love of Torah study and her difficulty in accepting a woman’s role in Judaism. Certainly, she must have been a very special woman, and I assume that she was, for a woman, quite learned. When Mekor Barukh was published there were still plenty of people alive who had known her and it would have been impossible to entirely fabricate her personality. The same can be said about Epstein’s report of the Netziv reading newspapers on Shabbat. This is not the sort of thing that could be made up. Let’s not forget that the Netziv’s widow, son (R. Meir Bar-Ilan) and many other family members and close students were alive, and Epstein knew that they would not have permitted any improper portrayal. It is when recording private conversations that one must always be wary of what Epstein reports.

A good deal has been written about the Rayna Batya story, and Dr. Don Seeman has referred to it as “the only record which has been preserved of a woman’s daily interactions with her male interlocutor over several months.”[15] When challenged about the historical accuracy of Epstein’s recollections, Seeman replied “that there is no evidence to indicate that R. Epstein invented these episodes out of whole cloth.”[16]

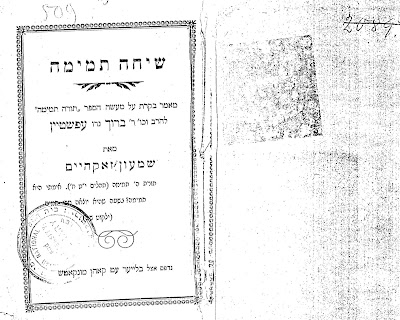

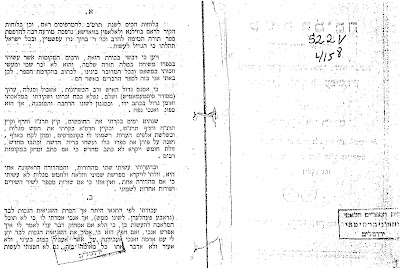

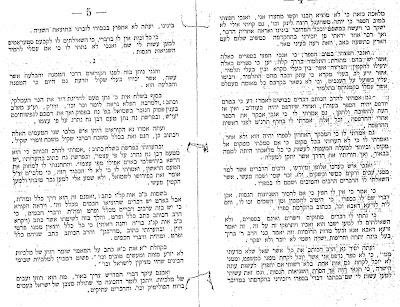

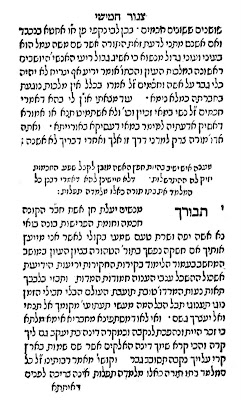

I will therefore explain how I concluded that the story is fictional. Let’s begin with the well-attested fact that Epstein was a plagiarizer. My assumption is that when dealing with someone who is not a reputable scholar, one must be very suspicious of what he or she writes when there is no outside evidence to back it up. In fact, when the Torah Temimah first appeared, the editor of this work published a booklet, Sihah Temimah, accusing Epstein of fraudulent behavior.[17] Here are the first few pages of this booklet.

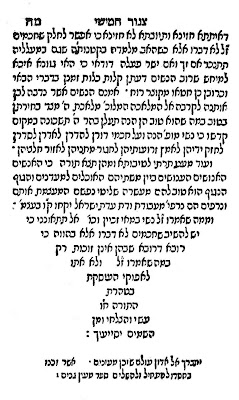

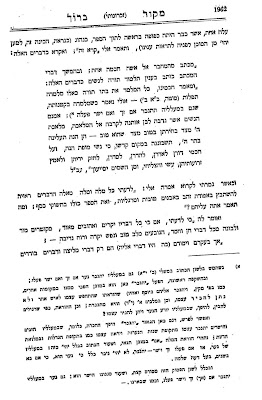

A central feature of his dialogue with Rayna Batya is her producing the book Ma’ayan Ganim by R. Samuel Archivolti. Here it states that mature women who have a desire to study Torah are to be encouraged (Mekor Barukh, p. 1962). Epstein, a young teenager, then attempts to refute her by arguing that the passage from Ma’ayan Ganim is not halakhic, but rather divrei melitzah. The whole dialogue, and in particular the part about her discovering the winning passage in Archivolti, is contrived and designed to lead the reader to sympathize with the fate of the poor woman.

In his Torah Temimah (Deut. ch. 11 n. 68) he cites the passage from Ma’ayan Ganim that as a teenager he supposedly argued against. Anyone reading Torah Temimah would assume that Ma’ayan Ganim is a regular halakhic work, as Epstein refers to it as She’elot u-Teshuvot.[18]

Although at the end of the passage he says that he doesn’t know who the author is, and that Tosafot Yom Tov calls him a grammarian, I believe that this is all part of the literary game he is playing. In other words, he wants to publicize Archivolti’s view, and then to “cover” himself cites Tosafot Yom Tov. In Mekor Barukh, after telling his story, he points out that Archivolti was also a great talmudist and that the only reason the Tosafot Yom Tov refers to him as a medakdek was because he was referring to him in his youth.[19]

Dan Rabinowitz, in his discussion of the issue, writes:

The entire famous Rayna Batya incident must now be called into serious question. Was Rayna Batya so ignorant as to confuse Ma’ayan Gannim with a legitimate book of halakha? How, then, do we reconcile this with her supposed profound learning? It cannot be that R. Epstein was unable to recognize the Ma’ayan Gannim for what it was, for he himself writes that he told his aunt of the true nature of Ma’ayan Gannim. But if he did know what it was, how is it that in his Torah Temima he refers to Ma’ayan Gannim as responsa—and yet in the same paragraph in the Torah Temima he seems to backtrack and wonder how it is that the Ma’ayan Gannim could innovate “new laws about women with reason alone?” The entire Rayna Batya episode is a highly problematic one, raising one perplexing question after another.[20]

As far as the first few questions are concerned, I can only say that the entire report of Rayna Batya discovering the relevant text in Ma’ayan Ganim was made up by Epstein. This book, which was published in Venice in 1553, is an extremely rare volume. There would have only been a few copies of this book in all of Lithuania. (In Torah Temimah Epstein also says that it is a rare book.) It is therefore impossible to imagine that the rebbetzin, sitting in Volozhin, would just so happen to come across this volume on her husband’s bookshelf. Of this, there can be no doubt, and I assumed that Epstein, who was a great bibliophile, later in life came across the book and in his desire to publicize its contents, created the dialogue with Rayna Batya.

Yet thanks to R. Yehoshua Mondshine’s recent article,[21] I see that I was mistaken in my assumption. The truth is that Epstein never even saw the book and thus did not know the true nature of Ma’ayan Ganim. He learnt of the relevant passage, which he places in Rayna Batya’s mouth, from an article that appeared in Ha-Tzefirah in 1894. We see this from the fact that the Ha-Tzefirah quotation mistakenly omits some words, and the same words are omitted in Mekor Barukh. This shows that his knowledge of this book came in 1894 and that he never discussed it with Rayna Batya, who died many years prior to this.

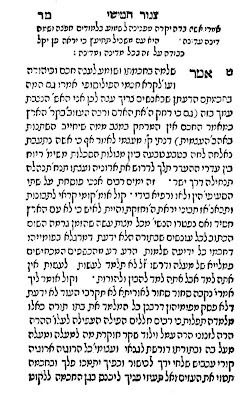

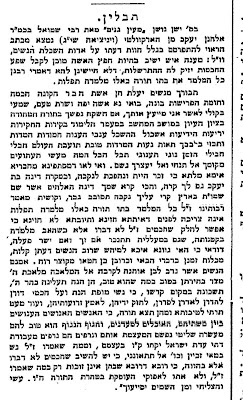

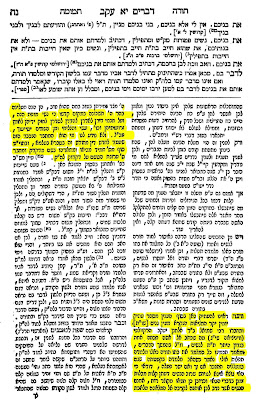

Now that we know where Epstein copied the text from, we can see another element of the literary game he played. He cites Ma’ayan Ganim as follows:

ומאמר חכמינו כל המלמד את בתו תורה כאלו מלמדה תפלות אולי נאמר כשהאב מלמדה בקטנותה.

Yet in Ha-Tzefirah it states:

מאמר רבותינו ז"ל כל המלמד בתו תורה כאלו מלמדה תפלות אינה צריכה לפנים דאיתתא חזינא ותיובתא לא חזינא כי אפשר לחלק שחכמים ז"ל לא דברו אלא כשהאב מלמדה בקטנותה.

Leaving aside the words Epstein omits, he has substituted אולי for אפשר לחלק. In doing so he softened Archivolti’s point. Whereas Archivolti was stating that one can distinguish between teaching a grown woman and a small girl, Epstein has Archivolti prefacing this idea with “perhaps”. I think this is part of Epstein’s confusing game. He wants to bring this view to the public’s attention, but he doesn’t want to come off as too radical. In fact, this אולי, which is his own creation, assumes a life of its own. Thus, in his letter to R. Hayyim Hirschensohn (Malki ba-Kodesh, vol. 6, p. 47), criticizing the latter’s view of teaching women Torah, Epstein writes:

In other words, Epstein invents the word אולי and inserts it into Archivolti’s letter, and then he uses this to criticize Hirschensohn! The chutzpah on Epstein’s part is astonishing, but as I see it this is all part of his game.

No one who has discussed Epstein and Rayna Batya was aware of his letter to Hirschensohn, so they could not point out the following obvious fact: When one looks at Mekor Barukh, which was published after his letter to Hirschensohn, one finds him telling Rayna Batya the exact same thing. It is obvious that he uses the language in his letter to Hirschensohn to create the following reply to Rayna Batya, that supposedly occurred some fifty years prior.

והן המחבר בעצמו כמו 'מודה במקצת' בזה, באמרו: 'ומאמר חכמינו' כל המלמד את בתו תורה כאלו מלמדה תפלות 'אולי נאמר כשמלמדה בקטנותה'; הרי שבעצמו אינו בטוח בדבריו, וכהוראת הלשון 'אולי' ולא ב"אולי" ולא ב"פן" מתירים מה שנאמר מפורש בתלמוד.

(It is possible that I am wrong in assuming that it was his positive view towards women studying Torah which explains why he created the story and cited Ma’ayan Ganim. Perhaps he was simply attempting to create a good story, or even some controversy, and that explains why he seems to be on both sides of the issue, as Dan Rabinowitz points out in the passage cited above.)

Here are the relevant pages in Ma’ayan Ganim, Ha-Tzefirah, Mekor Barukh, and Torah Temimah.

I know that there are people who are very upset at me, believing that I have given ammunition to those who chose to censor and withdraw My Uncle the Netziv. I make no apologies. We must combat falsehoods and plagiarism no matter where they emanate from. If, in the process, some of our own sacred cows are slaughtered, that is the price we must pay.

Returning to Mondshine, he is most concerned with the supposed dialogue between Epstein’s father, R. Yehiel Michel (the author of the Arukh ha-Shulhan), and the Tzemach Tzedek, R. Menachem Mendel Schneersohn. He sees it as an opportunity for Epstein to put all sorts of ideas, including criticisms of Hasidism, into the mouth of the great hasidic leader, something that if he did on his own would have brought down storms of criticism upon him. For example, he has the Tzemach Tzedek say that the hasidim have to be grateful for the opposition of the Vilna Gaon. Had it not been for the great dispute about Hasidism, and the Gaon’s strident opposition, the new movement might have led its followers out of the ranks of halakhic Judaism. (p. 1237). This idea was expressed by R. Kook (Ma’amrei ha-Re’iyah, p. 7) and was probably a common non-hasidic notion. But it is impossible to think that the Tzemach Tzedek would have ever expressed himself this way.

At the time that R. Yehiel Michel is said to have had his conversations with the Tzemach Tzedek, he was the rav of the Habad town Novozypkov.[22] In later years R. Abraham Chen and R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin served as rabbis of the town.[23] I know about this place because my grandmother’s second husband (who was like a grandfather to me) was from there. In fact, during World War One word came to the town that a certain group of Jews was being moved and would be passing through, and that among them was an outstanding young scholar named Shlomo Yosef Zevin. The townspeople came up with the necessary money to remove him from the group. He was chosen as the town’s rabbi and lived in my step-grandfather’s house for about six months. I read somewhere that the townspeople were followers of Kopys/Bobruisk, rather than Lubavitch. As R. Zevin was himself a Bobruisker, this would make sense. R. Yehiel Michel was himself born in Bobruisk, as was his son R. Baruch.

I always tell this story to Habad people in order to impress them with my yichus, that the great R. Zevin lived in my family’s house. Yet on two separate occasions after I told the story to young Habad shluchim, they replied, “Who is Rav Zevin?” It is also very rare to find a young Habadnik who has even heard of Kopust/Bobruisk. Yet without knowing about this it is impossible to understand how R. Zevin could have been a Zionist when the Lubavitcher rebbes were all anti-Zionist. After all, who ever heard of a hasid not following his Rebbe? The answer is that all Lubavitchers were Habad, but not all adherents of Habad were Lubavitch. The ignorance among some in Habad of their own movement probably shouldn’t surprise me, as I have met many hasidim who don’t have a clue about the history of the hasidic movement. And of course, how many Modern Orthodox know the first thing about Hirsch and Hildesheimer?

Mondshine assumes that one of the purposes of Epstein’s stories about his father and the Tzemach Tzedek is to build up his father’s halakhic reputation. His pesakim were subject to attack as being too liberal, and certainly in the hasidic world he was not accepted. In the Lithuanian world he was a much more important posek, and R. Joseph Elijah Henkin stated that in a dispute between the Mishneh Berurah and the Arukh ha-Shulhan, the Arukh ha-Shulhan is to be preferred.[24]

Yet many did not share R. Henkin’s viewpoint. A number of years ago I saw in one of R. Yitzhak Ratsaby’s books that he heard from some gedolim that one should not rely on the Arukh ha-Shulhan. I wrote to him objecting to this lack of respect for the Arukh ha-Shulhan, and also expressing my near certainty that the gedolim he referred to must have been Hungarian, for the Hungarian poskim never accepted the Arukh ha-Shulhan as an authoritative work. On Nov. 22, 1990, Ratsaby wrote to me:

בענין הגאון בעל ערוך השולחן, דוקא הדברים נובעים מליטא, והנני מפרש, הגר"י כהנמן זצ"