Marc B. Shapiro holds the Weinberg Chair in Judaic Studies, Department of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Scranton. He is a frequent contributor to the Seforim blog and his most recent posts are "Forgery and the Halakhic Process" and "Forgery and the Halakhic Process, part 2."

The post below was written as part of "Forgery and the Halakhic Process, part 2," which the baale ha-blog have split up for the convenience of the readers of the Seforim blog. As such, the footnotes continue from the conclusion of the previous post.

Responses to Comments and Elaborations on Previous Posts

by Marc B. Shapiro

1. Some were not completely happy with an example I gave of an error in the Chavel edition of Ramban in a previous post at the Seforim blog. So let me offer another, also from one of Ramban’s talmudic works (since that was the genre I used last time). In Kitvei Ramban, 1:413, Chavel prints the introduction to Milhamot ha-Shem. The Ramban writes:

In his note, Chavel explains the last words as follows:

Yet what Ramban means by למתחיל פרק אין עומדין are the children who begin their talmudic study with Tractate Berakhot. In other words, it is only the explanations and pesakim of the Rif that are obvious even to the beginner that have not been challenged.[21]

Regarding the example I gave in my last post at the Seforim blog, I forwarded to R. Mazuz one of the questions I received, which dealt with the form of the verb אסף found in the Ramban:

He answered as follows:

I must note, however, that while R. Mazuz’ understanding of Ps. 105:25 is in line with the Targum, this is not how the standard Jewish translations understand the verse.

(Shortly before writing this, I read about the outrage taking place in Emanuel, where in the local Beit Yaakov Sephardi students are being segregated from Ashkenazim to the extent that the two are not even permitted to play together. The Shas party has referred to this as nothing less than Apartheid, which it surely is.[22] What’s next? Mehadrin buses where the Sephardim sit in the back? Of course, when this happens the justification given will once again be that Ashkenazim are on a higher spiritual level and that’s why they can’t sit with Sephardim, not that they are racist, chas ve-shalom.

I mention this because R. Mazuz has made a comment that is relevant in this regard. Speaking to Ashkenazim who like to imagine the tannaim as “white”, he has called attention to Negaim 2:1, where R. Yishmael states that Jews are neither black nor white, but in between. In other words, the tannaim looked like Sephardim.)

2. One of the e-mails to me stated that we Modern Orthodox types love to criticize Artscroll, but how come we never point out errors in the Rav’s works. I can’t speak for anyone else, and it is true that the Rav has now assumed hagiographic standing, meaning that it has become much harder to criticize him or point out supposed errors in his works. However, if I detect what I think is an error I will definitely call attention to it, and I believe the Rav would expect as much, for this is a sign that you are taking his writing seriously. If the Rambam could make careless errors (the focus of a large section of my forthcoming Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters, available for pre-order on Amazon for only $8) then anyone can err, and it is no disrespect to call attention to these errors. There are actually a number of seforim which have sections in which they call attention to careless errors or things overlooked in the writings of various aharonim.

I understand why students of the Rav and his modern day hasidim might be reluctant to do so, but I never had any real relationship with him and can approach matters as an outsider. My only connection to the Rav was one summer in the Boston kollel (1985, the last year of the kollel. When I lived in Brookline in the 1990’s the Rav was no longer well). I was, however, privileged, together with Rabbi Chaim Jachter, to drive him back and forth to the Twersky’s house, and was thus able to hear some memorable things from him which I will record in a future post at the Seforim blog.

While on the topic of the Rav, let me also state that I used the Rav’s Machzor on Yom Kippur. I found the commentary uplifting and great credit must go to Dr. Arnold Lustiger for the effort he put into the volume. But there is one thing in the Machzor that annoyed me. It relates to what is called Hanhagot ha-Rav. This section includes all of the various practices of the Rav. This is certainly worth knowing and it wouldn’t have bothered me had it simply appeared at the beginning of the Machzor. But that is not the case.

Before I explain the problem, let me start with the following: A number of years ago I asked Prof. Haym Soloveitchik what the practice of his father was in a certain matter. His response was short and crisp. He told me that he never answers questions about his father’s hanhagot, and that to do so would be in total opposition to his father’s outlook.

I assume that today, if it was clear that my concern was of an academic nature, he would be more forthcoming. But back then I was another unknown kid writing to him trying to find some interesting practice of the Rav.

The way I understood Prof. Soloveitchik is that his father, like many gedolim, had practices that diverged from the mainstream. They came to these practices based on their original reading of the sources. Yet these were entirely private practices, reserved at most for other family members and perhaps some very close students. Because they went against the mainstream, they were not for mass consumption. Along these lines, R. Zevin reports, in his article on R. Hayyim Soloveitchik in his Ishim ve-Shitot, that it was such an outlook that explained why R. Hayyim did not want to decide practical halakhah. His original mind would lead him to overturn many accepted halakhot, yet he was not prepared to do so.

Returning to my problem with the Rav’s Machzor, we are told the following in this book: The Rav reversed the order of the final two phrases in the benediction ולירושלים in the Amidah, saying וכסא דוד מהרה לתוכה תכין prior to saying ובנה אותה בקרוב בימינו בנין עולם. This is the way the Sephardic siddurim have it, but certainly the Rav did not expect the entire Ashkenazic world to abandon their long-standing practice because of his practice. Yet when this paragraph (in minhah before Yom Kippur and maariv following Yom Kippur) appears there is a note telling people how the Rav read it. This is certainly encouraging people to abandon the Ashkenazic tradition in favor of the Rav’s reading. From all that I know about the Rav, this is not something he would have wanted.

Another example is that we are told that the Rav omitted the blessing הנותן ליעף כח as it is post-Talmudic. What possible purpose can such information have when provided on the page where this blessing appears, other than to lead people to omit the blessing? Is one to assume that the Rav really wanted people to reject the universal Ashkenazic practice? The Rav never got up at an RCA convention and told people that this is what they should do. Even at the Maimonides minyan and school there is no official minhag to omit this blessing. R. David Shapiro reported to me that almost all those who daven from the amud at the Maimonides synagogue minyan recite the blessing, and everyone does so at the Maimonides school minyan. Yet I wonder how many followers of the Rav are now omitting the blessing after seeing what appears in the Rav’s Machzor.

There are other examples, and as I said above, I don’t believe that this information should be secret. However, when you put it on the relevant pages of the Machzor, where the instructions to the worshipper are designed to be for practical application, you are telling people that if they see themselves as followers of the Rav, then they should follow his practices.

Since my correspondent made the false assumption that I would never point out an error of the Rav, and indeed almost challenged me, let me offer one. In Halakhic Man, page 30, in writing about halakhic man’s relationship with transcendence, the Rav writes:

While on the topic of the Rav, which is always of interest to people, let me note another error in the Rav’s writings, although this time the printer is at fault.[25] It has been reprinted a number times and the sentence has also appeared in translation. I realize that it is difficult to say that a text that appeared in the Rav’s own lifetime a few times without correction is a mistake, so I would love to be proven wrong. Yet it does seem that we are confronted with a typo. I would assume that the Rav never knew of the mistake, since people often don’t read their own material after it appears in print. In “U-Vikashtem mi-Sham”[26] the Rav writes:

Can there be any doubt that instead of הר"י the text should read רש"י?

R. Aharon Kafih, in his new book Minhat Aharon, 416, calls attention to a similar type of error in Shiurim le-Zekher Abba Mari, 1:14-15, n. 5 (I don’t have this book, so I can’t determine if Kafih is correct). Here the Rav writes:

Kafih writes:

3. A few people asked me about R. Mazuz’s reference to the homosexual poem in Judah Al-Harizi’s Tahkemoni (see my previous footnote 15, here). The relevant section, which appears in Gate 50, reads as follows

The gay poet speaks of the face of the young man, and this is actually a popular theme. In particular, the poets focus on the cheeks. There are a number of examples of this in R. Moses Ibn Ezra and Ibn Gabirol, but let give two examples from R. Judah Halevi:

This means “From his cheeks is my spice garden, as poison comes from his eyes.”[28] Brody notes that the first part is working off Song of Songs 5:13, where the woman says לחיו כערוגת הבושם, “His cheeks are as a bed of spices.” The last section means, to use a modern expression, “his look can kill.” That is, if he gives you non-approving look, it is crushing.

Elsewhere, Halevi writes:[29]

In Norman Roth’s translation: “Cheeks like coals of fire on a pavement of marble,” or as he paraphrases, “ruddy cheeks on pale skin.”[30]

I was asked about the meanings of these poems. I am hardly expert in this area and must leave it to others to determine the exact sense. There has been some dispute about them, although the current scholarly consensus is not something that will make the Orthodox community very happy.[31] I would like to believe that Nehemiah Allony is correct that all of these poems are to be understood as simple imitations of the dominant Arabic style, or as akin to the Song of Songs, where the love poems are to be understood allegorically as symbolizing spiritual matters. R. Shmuel ha-Nagid actually says this explicitly about his poems dealing with man-boy love.[32] (I think we can all agree that writing such verse today will certainly, and deservedly, get a rebbe fired![33])

The issue of homosexuality in the medieval Jewish world even came into the great conflict between R. Saadiah Gaon and David ben Zakkai. This was because the future gaon of Pumbeditha, R. Aaron ben Joseph ha-Kohen Sargado, who was on David ben Zakkai’s side, accused R. Saadiah of having homosexual relations with young men. If that is not bad enough, he adds that this was done with sifrei kodesh in the room and that witnesses can attest to it![34] This is, of course, an abominable accusation, and Harkavy, in his introduction (p. 223), apologizes for having to print what he terms

Of course, this is hardly the first example of rabbis, even great ones, hurling outrageous accusations at each other, but it is hard to find anything more disgraceful than this. The only example I can think of that is in this league is found in R. Jacob Emden’s Hit’avkut, 76b-77a, where he publicizes the disgusting accusation that R. Jonathan Eybeschütz fathered a child with his own daughter! If that’s not bad enough, this horrible story is repeated by R. Marvin Antelman in his Bekhor Satan, 37-38. (Antelman and his unusual writings deserve their own post at the Seforim blog.) It was regarding this sort of mudslinging that R. Zvi Yehudah Kook is quoted as follows (Gadol Shimushah [Jerusalem, 1994], 20):

Academic scholars such as Scholem have also noted the destructive affect on traditional Jewish society of the battle against Sabbatianism in general, and the Emden-Eybeschütz conflict in particular.

4. Since in my earlier post at the Seforim blog on the Eshkol I mentioned R. Yitzhak Ratsaby, and his negative attitude towards R. Joseph Kafih, I should note that one of Kafih’s students, R. Aharon Kafih (no relation) has recently published his Minhat Aharon.[35] On pages 211 n. 13 and 255 n. 45, there are some very strong attacks on Ratsaby, even accusing him of plagiarism. He also mentions how Ratsaby, when he needs to quote something from R. Yihye Kafih (known among his followers as מו"ר הישיש), will omit the last name so that people won’t know to whom he is referring. As Tamir Ratzon has pointed out, in the 1970’s Ratsaby referred positively to R. Joseph Kafih,[36] yet unfortunately, this is no longer the case. In fact, R. Aharon Kafih reports that Ratsaby tells people that it is forbidden to have any of R. Joseph Kafih’s books, and they must be burnt![37]

This dispute between Ratsaby and Kafih is simply a continuation of the great Yemenite dispute over the legitimacy of Kabbalah. It began with Kafih’s grandfather, R. Yihye, who stood at the head of the anti-Kabbalah forces.[38] Matters reached such extremes that the pro-Kabbalah side was successful in having R. Yihye thrown into jail (much like some mitnagdim conspired to have the same done to R. Shneur Zalman of Lyady). Here is the cover of a rare pamphlet published about 20 years ago. It is directed against both R. Yihye and R. Joseph.![]() 5. In my earlier post at the Seforim blog I referred to the anti-Habad book Ve-Al Titosh Torat Imekha. A few people asked me how they can get this book. The author, who wishes to remain anonymous so that he can be spared the personal price paid by anyone who goes up against Habad messianism, told me that when I quote his letter (see below). I should also announce that anyone who is interested in the book should write to him at the following address

5. In my earlier post at the Seforim blog I referred to the anti-Habad book Ve-Al Titosh Torat Imekha. A few people asked me how they can get this book. The author, who wishes to remain anonymous so that he can be spared the personal price paid by anyone who goes up against Habad messianism, told me that when I quote his letter (see below). I should also announce that anyone who is interested in the book should write to him at the following address

This book is interesting because you see that the author is somewhat conflicted. On the one hand, he recognizes how great the Rebbe was and all the positive things Habad has accomplished. On the other hand, he sees what is going on today and reluctantly concludes that the Rebbe himself crossed the line into heretical statements. I asked him why, if he thinks the Rebbe advocated heretical notions, he still shows him great respect? Why doesn’t he treat him as an enemy of traditional Judaism, as he would all others who advanced heresy? He wrote to me as follows.

So Rabbi Halevi feels that the Lubavitcher Rebbe denied certain of Maimonides Principles and yet he won’t regard him as a heretic because of all the good he accomplished. Once again, theological error in the Thirteen Principles, and the consequences that are supposed to result from this, have been trumped by other considerations. I don’t know how many more examples I need to bring where even the most traditional scholars are not prepared to accept Maimonides’ statement that rejection of one his Principles ipso facto removes one from the faith.[39] Of course, followers of the Rebbe will deny that he has violated any of Maimonides’ principles, but what is important for my purpose is that Rabbi Halevi has no doubt, and elaborates at length, on how the Rebbe has indeed done so. Yet despite this, he still does not regard him as a heretic.

6. In my earlier post at the Seforim blog I wrote that it is unfortunate that one of the only things R. Joseph Messas is known for is being the posek who permitted married women to uncover their hair. Someone wrote to tell me that he was not the only Moroccan rabbi to do so, as R. Moshe Malka, the late chief rabbi of Petah Tikvah, also ruled this way in his responsa Ve-Heshiv Moshe. (Malka published six volumes of responsa entitled Mikveh ha-Mayim; I don’t know why, for his last volume, he picked a new title). The correspondent began his e-mail regarding Malka by noting “I don’t know if you are aware . . . ” In fact, I am well aware of Rabbi Malka’s teshuvot on this topic, as they were addressed to someone I know very well. Since not everyone has access to the volume, here are the responsa. A quick internet search revealed that R. Irving Greenberg picked up on this source.[40] (He obviously saw it in one of R. Michael Broyde’s articles, as Greenberg also cites R. Yehoshua Babad, whose understanding of women’s hair-covering has been one of the bases for Broyde’s own lenient opinion in this matter, and it was Broyde who first publicized Babad’s view.)

![]()

![]()

![]()

7. In my last post at the Seforim blog I mentioned that the version וכל נוצר יורה in Yigdal is found in Birnbaum but not in earlier sources. Noam Kaplan pointed out that this is incorrect and that it is found in at least two early siddurim.[41] It is incredible that Abraham Berliner, who was an expert in manuscripts and early prayer books, overlooked this. R. Mazuz was also unaware of this version, and the Siddur ha-Meduyak only gives וכל נוצר יודה as an alternate. I am grateful to Noam for the correction. It is a good illustration of how the accumulated knowledge of many readers is a great help to all of us.

8. In my first post on the Eshkol, I raised the issue of whether one can accept a pesak even if one is convinced that it is incorrect from the standpoint of modern scholarship. I quoted Prof. David Berger’s view that it is acceptable to do so. Subsequently, I found that Berger also discusses this matter in a recent essay, where he raises the problem without advocating any position.

The legend goes back to Eldad ha-Dani and was accepted as authentic by the Radba

וקנאתי לרבנו הגדול רבי יצחק אלפאסי זכרונו לברכה קנאה גדולה, מפני שראיתי לחולקים על דבריו שלא השאירו לו כפי רב מחלוקותיהם ענין נכון בכל מה שדבר, ולא דבר הגון בכל מה שפרש, ולא פסק ראוי בכל מה שפסק, לא נשאר עם דבריהם בהלכות זולתי הדברים הפשוטים למתחיל פרק אין עומדין

In his note, Chavel explains the last words as follows:

רק בסוף הפרק הזה נמצאה השגה אחת מבעל המאור

Yet what Ramban means by למתחיל פרק אין עומדין are the children who begin their talmudic study with Tractate Berakhot. In other words, it is only the explanations and pesakim of the Rif that are obvious even to the beginner that have not been challenged.[21]

Regarding the example I gave in my last post at the Seforim blog, I forwarded to R. Mazuz one of the questions I received, which dealt with the form of the verb אסף found in the Ramban:

וחכמי הצרפתים אספו רובן אל עמן

He answered as follows:

אפשר לפרש אָסְפוּ מלשון ויאסוף רגליו אל המטה, ולשון קצרה הוא. ואפשר לומר אָסְפוּ כמו נאספו. ודומה לו (תהלים קה, כה) "הפך לבם לשנוא עמו", שהכוונה נהפך. אבל עדיף להגיה אֻסְפוּ מבנין פֻעַל אם כי לא מצינו דוגמא לזה במשמעות זו

I must note, however, that while R. Mazuz’ understanding of Ps. 105:25 is in line with the Targum, this is not how the standard Jewish translations understand the verse.

(Shortly before writing this, I read about the outrage taking place in Emanuel, where in the local Beit Yaakov Sephardi students are being segregated from Ashkenazim to the extent that the two are not even permitted to play together. The Shas party has referred to this as nothing less than Apartheid, which it surely is.[22] What’s next? Mehadrin buses where the Sephardim sit in the back? Of course, when this happens the justification given will once again be that Ashkenazim are on a higher spiritual level and that’s why they can’t sit with Sephardim, not that they are racist, chas ve-shalom.

I mention this because R. Mazuz has made a comment that is relevant in this regard. Speaking to Ashkenazim who like to imagine the tannaim as “white”, he has called attention to Negaim 2:1, where R. Yishmael states that Jews are neither black nor white, but in between. In other words, the tannaim looked like Sephardim.)

2. One of the e-mails to me stated that we Modern Orthodox types love to criticize Artscroll, but how come we never point out errors in the Rav’s works. I can’t speak for anyone else, and it is true that the Rav has now assumed hagiographic standing, meaning that it has become much harder to criticize him or point out supposed errors in his works. However, if I detect what I think is an error I will definitely call attention to it, and I believe the Rav would expect as much, for this is a sign that you are taking his writing seriously. If the Rambam could make careless errors (the focus of a large section of my forthcoming Studies in Maimonides and His Interpreters, available for pre-order on Amazon for only $8) then anyone can err, and it is no disrespect to call attention to these errors. There are actually a number of seforim which have sections in which they call attention to careless errors or things overlooked in the writings of various aharonim.

I understand why students of the Rav and his modern day hasidim might be reluctant to do so, but I never had any real relationship with him and can approach matters as an outsider. My only connection to the Rav was one summer in the Boston kollel (1985, the last year of the kollel. When I lived in Brookline in the 1990’s the Rav was no longer well). I was, however, privileged, together with Rabbi Chaim Jachter, to drive him back and forth to the Twersky’s house, and was thus able to hear some memorable things from him which I will record in a future post at the Seforim blog.

While on the topic of the Rav, let me also state that I used the Rav’s Machzor on Yom Kippur. I found the commentary uplifting and great credit must go to Dr. Arnold Lustiger for the effort he put into the volume. But there is one thing in the Machzor that annoyed me. It relates to what is called Hanhagot ha-Rav. This section includes all of the various practices of the Rav. This is certainly worth knowing and it wouldn’t have bothered me had it simply appeared at the beginning of the Machzor. But that is not the case.

Before I explain the problem, let me start with the following: A number of years ago I asked Prof. Haym Soloveitchik what the practice of his father was in a certain matter. His response was short and crisp. He told me that he never answers questions about his father’s hanhagot, and that to do so would be in total opposition to his father’s outlook.

I assume that today, if it was clear that my concern was of an academic nature, he would be more forthcoming. But back then I was another unknown kid writing to him trying to find some interesting practice of the Rav.

The way I understood Prof. Soloveitchik is that his father, like many gedolim, had practices that diverged from the mainstream. They came to these practices based on their original reading of the sources. Yet these were entirely private practices, reserved at most for other family members and perhaps some very close students. Because they went against the mainstream, they were not for mass consumption. Along these lines, R. Zevin reports, in his article on R. Hayyim Soloveitchik in his Ishim ve-Shitot, that it was such an outlook that explained why R. Hayyim did not want to decide practical halakhah. His original mind would lead him to overturn many accepted halakhot, yet he was not prepared to do so.

Returning to my problem with the Rav’s Machzor, we are told the following in this book: The Rav reversed the order of the final two phrases in the benediction ולירושלים in the Amidah, saying וכסא דוד מהרה לתוכה תכין prior to saying ובנה אותה בקרוב בימינו בנין עולם. This is the way the Sephardic siddurim have it, but certainly the Rav did not expect the entire Ashkenazic world to abandon their long-standing practice because of his practice. Yet when this paragraph (in minhah before Yom Kippur and maariv following Yom Kippur) appears there is a note telling people how the Rav read it. This is certainly encouraging people to abandon the Ashkenazic tradition in favor of the Rav’s reading. From all that I know about the Rav, this is not something he would have wanted.

Another example is that we are told that the Rav omitted the blessing הנותן ליעף כח as it is post-Talmudic. What possible purpose can such information have when provided on the page where this blessing appears, other than to lead people to omit the blessing? Is one to assume that the Rav really wanted people to reject the universal Ashkenazic practice? The Rav never got up at an RCA convention and told people that this is what they should do. Even at the Maimonides minyan and school there is no official minhag to omit this blessing. R. David Shapiro reported to me that almost all those who daven from the amud at the Maimonides synagogue minyan recite the blessing, and everyone does so at the Maimonides school minyan. Yet I wonder how many followers of the Rav are now omitting the blessing after seeing what appears in the Rav’s Machzor.

There are other examples, and as I said above, I don’t believe that this information should be secret. However, when you put it on the relevant pages of the Machzor, where the instructions to the worshipper are designed to be for practical application, you are telling people that if they see themselves as followers of the Rav, then they should follow his practices.

Since my correspondent made the false assumption that I would never point out an error of the Rav, and indeed almost challenged me, let me offer one. In Halakhic Man, page 30, in writing about halakhic man’s relationship with transcendence, the Rav writes:

It is this world which constitutes the stage for the Halakhah, the setting for halakhic man’s life. It is here that the Halakhah can be implemented to a greater or lesser degree. It is here that it can pass from potentiality into actuality. It is here, in this world, that halakhic man acquires eternal life! “Better is one hour of Torah and mitzvot in this world than the whole life of the world to come,” stated the tanna in Avot [4:17], and his declaration is the watchword of the halakhist.I am not an expert in scholarship on the Rav,[23] so I may have missed it, but I have not seen any articles on Halakhic Man which call attention to the fact that the Rav has misquoted Avot. What the Mishnah says is “Better is one hour of repentance and good deeds in this world than the whole life of the world to come.” Also surprising to me is that the learned translator did not mention the problem with the Rav’s quotation.[24] Is it possible that the Rav’s intellectualism and “halakho-centrism” led him to unknowingly replace בתשובה ומעשים טובים with בתורה ומצוות?

While on the topic of the Rav, which is always of interest to people, let me note another error in the Rav’s writings, although this time the printer is at fault.[25] It has been reprinted a number times and the sentence has also appeared in translation. I realize that it is difficult to say that a text that appeared in the Rav’s own lifetime a few times without correction is a mistake, so I would love to be proven wrong. Yet it does seem that we are confronted with a typo. I would assume that the Rav never knew of the mistake, since people often don’t read their own material after it appears in print. In “U-Vikashtem mi-Sham”[26] the Rav writes:

אבא מרי דיבר תמיד על אודות הרמב"ם. וכך היה עושה: היה פותח את הגמרא; קורא את הסוגיא. אחר כך היה אומר כדברים האלה: זהו פירושם של הר"י ובעלי-התוספות; עכשיו נעיין נא ברמב"ם, ונראה איך פירש הוא. תמיד היה אבא מוצא כי הרמב"ם לא פירש כמותם ונטה מן הדרך הפשוטה

Can there be any doubt that instead of הר"י the text should read רש"י?

R. Aharon Kafih, in his new book Minhat Aharon, 416, calls attention to a similar type of error in Shiurim le-Zekher Abba Mari, 1:14-15, n. 5 (I don’t have this book, so I can’t determine if Kafih is correct). Here the Rav writes:

ועיין ברמב"ן סוף מס' פסחים (במלחמות) שמתוך דבריו וביאורו בירושלמי . . . עולה שאם לא קרא את ההלל בביהכ"נ חייב לברך על ההלל בהגדה

Kafih writes:

אחר המחילה נראה שיש כאן טעות, ומדובר בר"ן ויובאו דבריו לקמן בגוף החיבור ד"ה וזה שאמרו בירושלמי

3. A few people asked me about R. Mazuz’s reference to the homosexual poem in Judah Al-Harizi’s Tahkemoni (see my previous footnote 15, here). The relevant section, which appears in Gate 50, reads as follows

לאיש עשה שיר מלא זמה וטומאה

לו שר בנו עמרם פני דודי מתאדמים העת שתות שכר

ויפי קוצותיו והוד יופיו לא חק בתורתו ואת זכר

The translation is:לו שר בנו עמרם פני דודי מתאדמים העת שתות שכר

ויפי קוצותיו והוד יופיו לא חק בתורתו ואת זכר

To a man who wrote a poem full of filth and lewdnessFollowing this, Al-Harizi, quotes the poems of nine others, and himself, who condemn the homosexual poet. Some contemporary readers might be shocked to see the language used. It is certainly not anything that those preaching a message of “hate the sin and love the sinner” vis-à-vis the gay community – and this includes R. Chaim Rapoport, the world’s expert on halakhah and homosexuality – would endorse. For example, one of the poems reads:

Were Amram’s son to see my friend’s face

Blushing when he drinks strong drink

And for the loveliness of his locks and the splendor of his beauty

He would not have inscribed in his Torah

“If a man lie with mankind” (cf. Lev. 20:13).[27]

מוכר קדושת אל בעד טומאה מהר ליד הורג יהי נמכר

He who sells the sanctity of God for defilementAnother reads:

Let him quickly be sold into the hand of the slayer.

שדי שלח מהר עדי מות האיש אשר דתך בחטא מכר

Almighty, deliver speedily into the hand of deathIn fact, all of the poems quoted by Al-Harizi call for the gay poet to be struck down, in one way or another.

The man who has sold Thy law into sin.

The gay poet speaks of the face of the young man, and this is actually a popular theme. In particular, the poets focus on the cheeks. There are a number of examples of this in R. Moses Ibn Ezra and Ibn Gabirol, but let give two examples from R. Judah Halevi:

מלחייו עדן בשמי כאשר מעיניו סמי

This means “From his cheeks is my spice garden, as poison comes from his eyes.”[28] Brody notes that the first part is working off Song of Songs 5:13, where the woman says לחיו כערוגת הבושם, “His cheeks are as a bed of spices.” The last section means, to use a modern expression, “his look can kill.” That is, if he gives you non-approving look, it is crushing.

Elsewhere, Halevi writes:[29]

לחי כרצפת אש ברצפת שש

In Norman Roth’s translation: “Cheeks like coals of fire on a pavement of marble,” or as he paraphrases, “ruddy cheeks on pale skin.”[30]

I was asked about the meanings of these poems. I am hardly expert in this area and must leave it to others to determine the exact sense. There has been some dispute about them, although the current scholarly consensus is not something that will make the Orthodox community very happy.[31] I would like to believe that Nehemiah Allony is correct that all of these poems are to be understood as simple imitations of the dominant Arabic style, or as akin to the Song of Songs, where the love poems are to be understood allegorically as symbolizing spiritual matters. R. Shmuel ha-Nagid actually says this explicitly about his poems dealing with man-boy love.[32] (I think we can all agree that writing such verse today will certainly, and deservedly, get a rebbe fired![33])

The issue of homosexuality in the medieval Jewish world even came into the great conflict between R. Saadiah Gaon and David ben Zakkai. This was because the future gaon of Pumbeditha, R. Aaron ben Joseph ha-Kohen Sargado, who was on David ben Zakkai’s side, accused R. Saadiah of having homosexual relations with young men. If that is not bad enough, he adds that this was done with sifrei kodesh in the room and that witnesses can attest to it![34] This is, of course, an abominable accusation, and Harkavy, in his introduction (p. 223), apologizes for having to print what he terms

דברי שמצה ונבול פה שאין הנפש היפה סובלתם

Of course, this is hardly the first example of rabbis, even great ones, hurling outrageous accusations at each other, but it is hard to find anything more disgraceful than this. The only example I can think of that is in this league is found in R. Jacob Emden’s Hit’avkut, 76b-77a, where he publicizes the disgusting accusation that R. Jonathan Eybeschütz fathered a child with his own daughter! If that’s not bad enough, this horrible story is repeated by R. Marvin Antelman in his Bekhor Satan, 37-38. (Antelman and his unusual writings deserve their own post at the Seforim blog.) It was regarding this sort of mudslinging that R. Zvi Yehudah Kook is quoted as follows (Gadol Shimushah [Jerusalem, 1994], 20):

הדגיש בכאב עצום שתחילת המחלוקות החריפות בין גדולים מעבר לאמות מידה מקובלות של מחלוקות, התחילו מבית-מדרשו של רבי יעקב עמדין

Academic scholars such as Scholem have also noted the destructive affect on traditional Jewish society of the battle against Sabbatianism in general, and the Emden-Eybeschütz conflict in particular.

4. Since in my earlier post at the Seforim blog on the Eshkol I mentioned R. Yitzhak Ratsaby, and his negative attitude towards R. Joseph Kafih, I should note that one of Kafih’s students, R. Aharon Kafih (no relation) has recently published his Minhat Aharon.[35] On pages 211 n. 13 and 255 n. 45, there are some very strong attacks on Ratsaby, even accusing him of plagiarism. He also mentions how Ratsaby, when he needs to quote something from R. Yihye Kafih (known among his followers as מו"ר הישיש), will omit the last name so that people won’t know to whom he is referring. As Tamir Ratzon has pointed out, in the 1970’s Ratsaby referred positively to R. Joseph Kafih,[36] yet unfortunately, this is no longer the case. In fact, R. Aharon Kafih reports that Ratsaby tells people that it is forbidden to have any of R. Joseph Kafih’s books, and they must be burnt![37]

This dispute between Ratsaby and Kafih is simply a continuation of the great Yemenite dispute over the legitimacy of Kabbalah. It began with Kafih’s grandfather, R. Yihye, who stood at the head of the anti-Kabbalah forces.[38] Matters reached such extremes that the pro-Kabbalah side was successful in having R. Yihye thrown into jail (much like some mitnagdim conspired to have the same done to R. Shneur Zalman of Lyady). Here is the cover of a rare pamphlet published about 20 years ago. It is directed against both R. Yihye and R. Joseph.

5. In my earlier post at the Seforim blog I referred to the anti-Habad book Ve-Al Titosh Torat Imekha. A few people asked me how they can get this book. The author, who wishes to remain anonymous so that he can be spared the personal price paid by anyone who goes up against Habad messianism, told me that when I quote his letter (see below). I should also announce that anyone who is interested in the book should write to him at the following address

5. In my earlier post at the Seforim blog I referred to the anti-Habad book Ve-Al Titosh Torat Imekha. A few people asked me how they can get this book. The author, who wishes to remain anonymous so that he can be spared the personal price paid by anyone who goes up against Habad messianism, told me that when I quote his letter (see below). I should also announce that anyone who is interested in the book should write to him at the following addressהרב יב"א הלוי, ת"ד 57615, ירושלים

This book is interesting because you see that the author is somewhat conflicted. On the one hand, he recognizes how great the Rebbe was and all the positive things Habad has accomplished. On the other hand, he sees what is going on today and reluctantly concludes that the Rebbe himself crossed the line into heretical statements. I asked him why, if he thinks the Rebbe advocated heretical notions, he still shows him great respect? Why doesn’t he treat him as an enemy of traditional Judaism, as he would all others who advanced heresy? He wrote to me as follows.

זו אכן שאלה שכבר נשאלתי עליה מרבים וטובים, והתשובה היא שאם היה מדובר בסתם אדם אז בודאי שאסור להתייחס אליו בכבוד, לעומת זאת הרבי האחרון מחב"ד, שלמרות הבקורת העזה עליו, הוא ג"כ עשה פעולות גדולות והפיץ הרבה תורה בעולם, ולכן צריך לחפש ללמד עליו זכות (הגם שאני בעצמי אינני יודע מה אפשר לומר עליו זכות במה שכתב שהוא "מרגיש" שהקב"ה התלבש בו). ולכן העדפתי לעשות פלגינן, אליו אישית להתיחס בכבוד, ולעומת זאת לכתוב שדבריו הם מנוגדים לי"ג עיקרים, ומי שרוצה להסיק מזה מסקנא לגבי הרב בעצמו עושה זאת על דעתו, כי באמת לא ידוע לי איך צריך להתיחס למי שמצד אחד כתב דברים נוראים ומצד שני הפיץ הרבה תורה, ודוק והבן

So Rabbi Halevi feels that the Lubavitcher Rebbe denied certain of Maimonides Principles and yet he won’t regard him as a heretic because of all the good he accomplished. Once again, theological error in the Thirteen Principles, and the consequences that are supposed to result from this, have been trumped by other considerations. I don’t know how many more examples I need to bring where even the most traditional scholars are not prepared to accept Maimonides’ statement that rejection of one his Principles ipso facto removes one from the faith.[39] Of course, followers of the Rebbe will deny that he has violated any of Maimonides’ principles, but what is important for my purpose is that Rabbi Halevi has no doubt, and elaborates at length, on how the Rebbe has indeed done so. Yet despite this, he still does not regard him as a heretic.

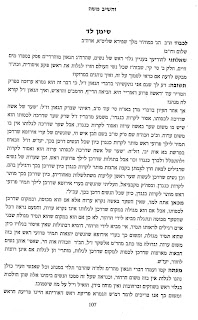

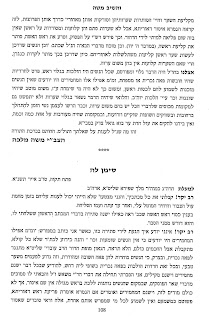

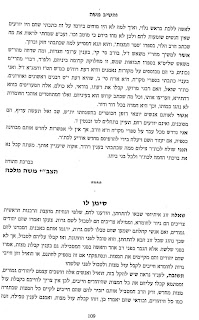

6. In my earlier post at the Seforim blog I wrote that it is unfortunate that one of the only things R. Joseph Messas is known for is being the posek who permitted married women to uncover their hair. Someone wrote to tell me that he was not the only Moroccan rabbi to do so, as R. Moshe Malka, the late chief rabbi of Petah Tikvah, also ruled this way in his responsa Ve-Heshiv Moshe. (Malka published six volumes of responsa entitled Mikveh ha-Mayim; I don’t know why, for his last volume, he picked a new title). The correspondent began his e-mail regarding Malka by noting “I don’t know if you are aware . . . ” In fact, I am well aware of Rabbi Malka’s teshuvot on this topic, as they were addressed to someone I know very well. Since not everyone has access to the volume, here are the responsa. A quick internet search revealed that R. Irving Greenberg picked up on this source.[40] (He obviously saw it in one of R. Michael Broyde’s articles, as Greenberg also cites R. Yehoshua Babad, whose understanding of women’s hair-covering has been one of the bases for Broyde’s own lenient opinion in this matter, and it was Broyde who first publicized Babad’s view.)

7. In my last post at the Seforim blog I mentioned that the version וכל נוצר יורה in Yigdal is found in Birnbaum but not in earlier sources. Noam Kaplan pointed out that this is incorrect and that it is found in at least two early siddurim.[41] It is incredible that Abraham Berliner, who was an expert in manuscripts and early prayer books, overlooked this. R. Mazuz was also unaware of this version, and the Siddur ha-Meduyak only gives וכל נוצר יודה as an alternate. I am grateful to Noam for the correction. It is a good illustration of how the accumulated knowledge of many readers is a great help to all of us.

8. In my first post on the Eshkol, I raised the issue of whether one can accept a pesak even if one is convinced that it is incorrect from the standpoint of modern scholarship. I quoted Prof. David Berger’s view that it is acceptable to do so. Subsequently, I found that Berger also discusses this matter in a recent essay, where he raises the problem without advocating any position.

In the realm of concrete decision-making in specific instances, it is once again the case that the impact of academic scholarship does not always point in a liberal direction. In other words, the instincts and values usually held by academics are not necessarily upheld by the results of their scholarly inquiry, and if they are religiously committed, they must sometimes struggle with conclusions that they wish they had not reached Thus, the decision that the members of the Ethiopian Beta Israel are Jewish was issued precisely by rabbis with the least connection with academic scholars. The latter, however much they may applaud the consequences of this decision, cannot honestly affirm that the origins of the Beta Israel are to be found in the tribe of Dan; here, liberally oriented scholars silently, and sometimes audibly, applaud the fact that traditionalist rabbis have completely ignored the findings of contemporary scholarship.[42]I have to say that I too struggled with this question, as I was involved in the Ethiopian Jewry cause.[43] My first trip there, in 1987, was memorable, as we were the first group allowed into the villages of Gondar after Operation Moses. (It was also great to be together with Rabbi Dr. Ari Zivotofsky, who in recent years has done such important work on various communal traditions that are in danger of being forgotten.) Yet I vividly recall how even then, when I was quite young, I knew that the notion of the Ethiopian Jews being descended from Dan was a legend without any historical value. The Ethiopians themselves never claimed that they had any connection to the tribe of Dan.

The legend goes back to Eldad ha-Dani and was accepted as authentic by the Radba